JAYNE SHATZ POTTERY

PhD-Prehistoric Ceramics

MA- Pottery and Sculpture

BA - Art History here to add text.

WOMEN'S CONTRIBUTION TO THE CERAMIC FIELD.

It has been the assumption of the modern world that work that dealt with great physical strength and technical expertise was solely man’s work. Ceramics is one of those fields that commands the integration of strength, technical mastery and artistic imagination. Ceramics has been regarded as a man’s art in many cultures; men produced most of the pottery in China, Japan, Korea, Greece and Rome. In late 19th century Europe and the United States, women emerged onto the ceramic scene in art potteries as “decorators”, painting surfaces with beautifully executed images, while men produced the forms, either by hand or poured molds.

However, during ancient times it was women who worked the clay. Our story begins during the prehistoric Ice Age around 27,000 BPE, (Before the Present Era) in a small section of land in what is now known as Czechoslovakia. In this frozen tundra there existed a green oasis, void of ice. A clan lived there with a female shaman that produced kiln fired ceramic sculptures that we now call the Venus Figurines. Her kiln had an underground flue that was fueled by bones; this firing technique created the rich black carbon surface on the beautiful six-inch forms. To imagine a woman firing a kiln almost thirty thousand years ago is a phenomenal concept to grasp! But there she was, breathing in the cool night, listening to the sounds of air being forced through a flue and concentrating on the day's work....... Sound familiar?

She was the beginning of women’s illustrious endeavor in clay. Women have always been capable of producing high quality ceramic work; many cultures existed where women solely produced elegantly coiled pottery while men took care of the homestead. The North and South American Indians and the Neolithic Middle Eastern cultures provide much evidence to this distinction of roles. In these societies, women were the pot makers, creating utensils for the home life. Their job was essential to the sustenance of their families, clans and homesteads. Pottery was used for eating, cooking and the storing of foodstuffs. For many societies, ceramic ware was also a source of trade and income. The Neolithic cultures, 10,000-2,000 BPE, elevated this agrarian system into a complex way of living. In the midst of this utilitarian focus, our ancient potters exhibited a spectacular imagination and creative sensibility that produced artfully decorated ware equal to our modern day artists. With the invention of the potter’s wheel around 6000 BPE, men began to take over the production of pottery, which slowly evolved into a mass production business. The onset of machinery brought about the demise of hand made work and the bourgeoning industrialized world took hold.

As the centuries advanced, men routinely produced the ceramics; women were basically denied most opportunities to work in clay. Women had to be extremely unique in order to break into this man’s field. As the 19th century emerged, a new way of thinking was on the horizon, and women were anxious to be represented and contribute their unique viewpoint. Women eagerly made their mark in the ceramic field, as this period witnessed a substantial movement in women’s contribution to ceramics.

This lecture historically traces the accomplishments of women ceramists and their prominent position in the ceramic field.

DOLNI VESTONICE VENUS

27,000 BPE

The Upper Paleolithic, or Ice Age, was a time of spontaneous evolution in the development of art, music, and tool technology. The uncovering of the Dolni Vestonice Venus from the cave site in Czechoslovakia is of special interest to ceramists. In that ice free corridor of Czechoslovakia a grouping of three huts was discovered in close proximity to one another, dating from 27,000 BPE. Inside each hut were hearths ringed with flat stones, made from a shallow depression in the flooring. The two larger huts had five hearths each and it is believed that they were the communal dwellings of a hunting clan. In particular, the smallest hut with similar flooring was entirely enclosed in a wall of limestone and clay. This hut’s hearth provided a spectacular discovery in ceramic history. A prehistoric kiln in the shape of a "beehive" was surrounded by thousands of clay pellets, attesting to a ceramic modeler’s work. Along with these pellets were found fragments of the heads of two bears and a fox and some unfinished statuettes. Some archaeologists believe this 30,000-year-old kiln to be the oldest kiln ever to be discovered. It is thought to be the home of a Paleolithic Shaman; the sacred hut where the figurines of women and beasts used in fertility rites were produced and fired. This Shaman was assumed to be a woman, as the men in the clan were hunters, while the women were responsible for all home life activities.

A small black figurine sculpted from local clays and bone ash was found intact at this kiln site, with other shards of similar forms. These earliest "Venus" figurines displayed large voluminous breasts, angular shoulders, and legs tapering down to small rounded points. These sculptural forms indicated that they were held as idols in ceremonial fertility rituals. The tops of the heads had four holes made to hold flowers, leaves, or feathers, symbolizing the successful changing of the seasons, which were attributed to the fertility of the goddesses. The female figure predominates Paleolithic small sculpture. She personifies the continuity of the species and the magical invocation of the survival of the race.

Dolni Vestonice, Venus Figurine

27,000 BPE, 9 " h

Fertility Goddess Catal Hyuk

Anatolia, (Tureky), 6000 BPE

THE FERTILITY GODDESS, CATAL HUYUK, TURKEY, 6000 BPE

This fertility figurine, like the Dolni Vestonice Venus, was sculpted in earthenware clay and It displays the large breasts, hips and thighs that represent fertility. This ubiquitous sculpture depicted the ancient and primitive worlds’ feminine attributes of fertility and the survival of the species. Most often these sculptures were small, used in very intimate ceremonies that involved only women. It should be noted that Catal Huyuk developed into one of the largest ceramic centers in the Mid East, making the availability of clay and firing equipment easily obtainable. The importance of ritualistic ceremonies was still a part of the life cycle of this very stable agrarian society

JOMON POTTERY, JAPAN, 12000-1500 BPE

Ancient Japanese pottery dates back over twelve thousand years ago to the wondrous ceramics of the Jomon era; it is understood that this culture produced the world’s first coiled pots. As with most Neolithic cultures, many archaeologists believe that women produced these pots. Jomon potters enjoyed a peaceful lifestyle due to their protective island setting, which enabled them to develop their artistry, especially in ceramics. Their pottery was used in similar ways as most Neolithic cultures, as food storage and cooking vessels. Their work was fired in above ground bonfires, depositing a beautiful carbon surface on the vessels. Their ceramics is most notably identified by vigorously applied coil decoration and also by the pressing of cords onto the damp clay surface. Jomon actually means, “cord markings”. Notice the frenetic decorative coils and waving soaring rims that exemplify this beautiful ancient ware. The Jomon ware of prehistory is as impetuous and alive as today’s most contemporary work.

Jomon Pottery, Japan, 12000-1,5000 BPE, coil built earthenware

The potter’s wheel was invented around 6000 BPE, and within a thousand years, it was widely used. By the conclusion of the Neolithic period, 1500-1000 BPE, most of the ceramic work evolved into businesses, overseen by men. Primitive cultures continued to survive in areas such as Africa, Australia and South America, where women continued to be the main pottery makers. In the Egypt, Greek, and Roman cultures, 3000 BPE-1000 PE, women slaves might have helped in the preparation of clay, but the actual great pottery makers were men. In the Far East, ancient low-fired techniques gave way to the high-fired stoneware of China, Japan and Korea, where ceramics developed into a major art form complete with a hierarchal designation of male dominated family potteries. Similarly, in 15th century Italy, the della Robbia family spawned several generations of men producing tin glazed wall sculptures, representing the great ceramics of Europe. Many Renaissance ceramists, patronized by the wealthy nobility, were mostly men that produced intricately painted majolica plates, vases and sculptures. There might have been some women working in these male dominated clay factories, but their work did not demonstrate a substantial quantity or patronage to be viewed as a body of work. As ceramics evolved worldwide, much of the primitive society’s ceramic work began to diminish, such as our own Native American ware.

So it appears that this was the demise of women working in the ceramic field. However, this was just a temporary anomaly.xt.

I WILL NOW PRESENT SOME VERY IMPORTANT FACTS

WE NEED TO UNDERSTAND THAT SEVERAL CENTURIES ELAPSED in which women were not making a substantial amount of pottery; men took over traditional pottery manufacturing and turned it into an industry. This is just a fraction of time in the total history of ceramic production. Ancient women potters produced great work from 27,000 BPE until about 1500 BPE. That constitutes 25,000 years of clay production. Viewed in this light, the period between 1500 BPE to 1800 PE (Present Era), represents 3000 years out of a total of 25,000 years that women have been working in clay. By the late 1800’s, women re-emerged onto the ceramic scene, working in art potteries, schools, private studios and industry. Their enduring presence ascended into the ceramic oeuvre once more!

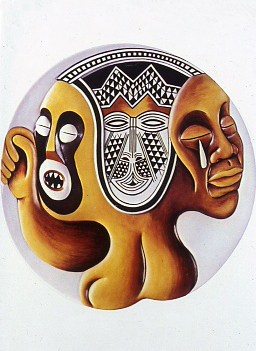

CONTEMPORARY PRIMITIVE CERAMICS

There are places throughout the world, such as this community in Funjoho, Africa, that still employ primitive techniques to create their work. In some cases, the society as a whole lives a primitive lifestyle and fires their work much as their ancestors had.

.

In modern societies, such as ours, contemporary artists have rediscovered primitive forming and firing techniques. Sometimes, these techniques are customized with modern tools and equipment, such as substituting metal garbage cans to fire the work instead of in ground pits, and enhancing the ware with chemicals.

Funjoho, Africa, 1900's,

Contemporary Primitive, 1990's,

An example of modern day pit fired ceramics is shown here through the work of New York ceramist, Colleen O’Sullivan, b. 1951, who employs both traditional and adapted primitive firing techniques. These beautiful vessels are pit fired with added oxides.

Colleen O'Sullivan, Pit Fired Bowl, New York, 2007

Colleen O'Sullivan, Pit Fired Urn, New York, 2007

AMERICAN ART POTTERIES

The age of the American Art Potteries flourished at a time when not only was our country experiencing a surge in manufacturing, but also an ecliptic escalation in artistic creativity. The flowery, yet somewhat decadent motifs of European Art Nouveau brought about a diverse amalgamation into the sleek clean lines of Modernism and Art Deco.

t.

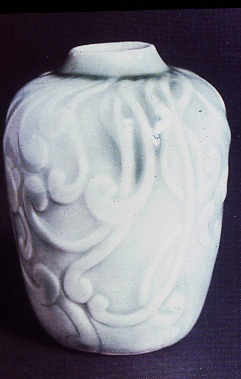

The American Art Potteries acclaimed worldwide attention to ceramic wares that were being produced in our country. Suddenly, individual artists were becoming as well known as the industriously producing potteries. In the latter part of the 19th century, men would throw master vessels and molds would be created for mass production of their work. Then, women were hired as decorators, painting artistic masterpieces on the ceramic forms. These art potteries gained notoriety primarily for their decorators. Being a decorator was one of the few areas of employment that was considered respectable for a woman in this male dominated American industry. Many women became decorators just to be able to have a chance to work outside the home. Rookwood Pottery developed into one of the finest art potteries in the world that employed mostly women.

An interesting and successful American Art Pottery was the extraordinary Arequipa Sanatorium, which functioned from 1911-1918. This unique pottery functioned predominately by the work of female tuberculosis patients.

After the 1906 earthquake and fires of San Francisco, the dust and ash filled air created a tuberculosis epidemic. Dr. Philip King Brown founded the Arequipa Sanatorium as a country retreat for women to recuperate from tuberculosis.

Besides bed rest, handcrafting pottery was seen as a therapeutic activity that provided work for these women, thus diminishing the stigma of charity. This philosophy complemented the bourgeoning ideals of the Arts and Crafts Movement in America. This movement, which originated in England, supported the production of hand made objects over those mass-produced by industry.

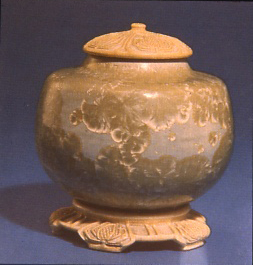

Rookwood Pottery, 1900

Arequipa Ware, 1911-1918

By the late 1850’s there were a great many art potteries; the work became very decorative rather than utilitarian and ultimately became a leading collectible. The Art Potteries became the foundation for women’s re-emergence into the ceramic scene. Several women were able to evolve beyond solely being decorators; they began producing the ceramic forms as well as decorating them. These women became the earliest studio potters. ext.

MARY LOUISE MCLAUGHLIN, 1847-1939

Mary Louise McLaughlin was a leader in the art pottery movement in America. Mary Louise worked in Cincinnati, and with several other women showed their ceramics at the nation's Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. These women’s work was far superior to that of any other city on display. Mary Louise examined the art pottery of France's Havilland & Co. His decorations were painted under the glaze, not over the glaze. This technical advancement was omnipotent to ceramic decorators and Mary Louise desired to develop this technique.

Mary Louise McLaughlin, Losanti Vase, 1892

MARY CHASE PERRY STRATTON, 1867-1961

Mary Chase Perry Stratton was born in Michigan, and was co-founder with Horace James Caulkins of the Pewabic Pottery, in 1903. The pottery was named after an old copper mine in Michigan. In 1918 she married William Stratton. Under her leadership, Pewabic Pottery produced architectural tiles, lamps and vessels. The Pewabic Pottery became known far and wide for its iridescent glazes, and was used in churches, libraries, schools and public buildings.

Mary Chase established the ceramics department at the University of Michigan and taught there. She also taught at Wayne State University. In 1947, she received the highest award in the American ceramic field, namely the Charles Fergus Binns Medal.

Mary Chase worked at the pottery until her death in 1961 at the age of 94. Today Pewabic Pottery offers classes, workshops, lectures, internships and residency programs for potters of all ages.

Mary Chase Perry Stratton, Pewabic Pottery,

Detroit, Michigan,1929

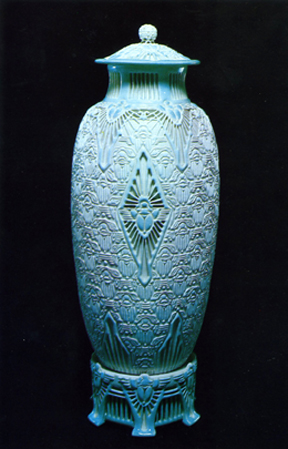

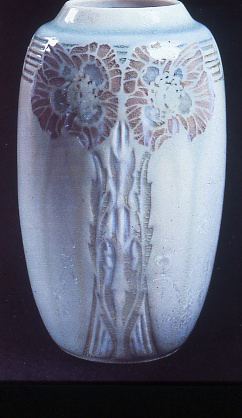

ADELAIDE ALSOP ROBINEAU, 1865-1929

Adelaide Alsop Robineau, from Syracuse, NY, reached international fame. Adelaide was an American painter and potter from Syracuse, NY, who began exploring porcelain after having worked as a china painter. In 1899 Adelaide became involved as editor for the ceramics publication, Keramic Studio, a pioneering American ceramics magazine. It was through an article published in that magazine that she became interested in porcelain, subsequently studying porcelain making under the renown Charles Binns, who taught at Alfred University between 1900 and 1931.

Porcelain became the medium with which she would create intricately incised works, often of a very ornate nature. Her 1910 'Scarab Vase' is both beautiful as well as a demonstration of endurance and fortitude; it is regarded as being of particular importance. Its actual title is The Apotheosis of the Toiler, a reference to the 'unknown potter', but it is also known as the Scarab Vase, because of its scarab theme. It depicts the scarab bug slowly climbing upward to the top of the vessel, where he would reap the rewards of his ascent.

Adelaide is said to have spent 1000 hours working on this particular piece. When it emerged from the bisque firing, it had numerous cracks that her teacher told her were impossible to repair. But Adelaide filled the cracks with bisque paste and painstakingly restored the piece and glazed it. When it came out of the kiln it was perfect- attesting to her remarkable work ethic, hence the title of the piece. You can usually see the Scarab Vase on exhibit in its home at the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, NY. Not only were Adelaide’s carvings complex, but her sumptuous glazes, and classical forms created the Robineau “ideal”. Adelaide enjoyed many successes, in particular the 1911 awarding of the Grand Prize at the International Exposition of Decorative Arts at Turin in Italy.

Adelaide Robineau brought Europe’s attention to the United States, establishing America as a leader in the world ceramic community

Adelaide Robineau carving the Scarab Vase

Adelaide Robineau, The Scarab Vase, The People's University, St. Louis, Missouri, 1910

Adelaide Robineau, Poppy Vase, 1910

Adelaide Robineau, 1904

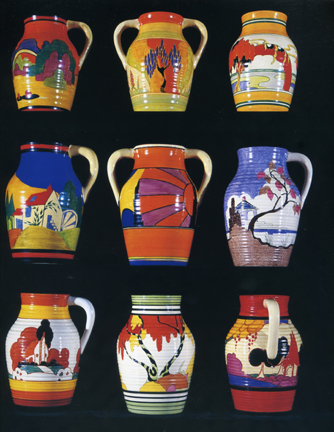

CLARICE CLIFF -1899 -1972

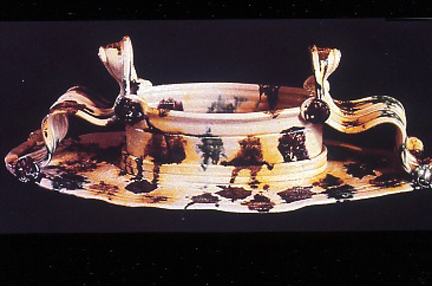

Clarice Cliff was a ceramic artist emerging from the Modernist period and actively working during 1922 to 1940. She was born in England, a descendent of Josiah Wedgwood. At the age of 13 she started working in the potteries, and studied at the Burslem School of Art in the evenings. Her work was unlike most of the pottery produced during this time, as her color palette was one of a vibrant primary color scheme; her colors looked like they were poured directly out of a painter’s tube. Her forms were modeled in true modernist angles, sleek and bold. She produced a vast quantity of work in two lines called “Bizzare” and “Fantasque” Wares. To the surprise of the company’s salesmen, this was immediately popular. She was provided with her own studio and another painter to assist, rapidly expanded to a team of around 70 young painters who hand painted the wares under her direction. Through the Depression her wares continued to sell in volume at high prices. Her Bizarre and ware was sold throughout the world, in North America, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, but not in mainland Europe.

By 1929 Clarice was designing her own shapes. The forms maintained the very angular Art Deco and Modernist trends moving into abstract and cubist styles. In 1930 she was appointed Art Director to Newport Pottery and A. J. Wilkinson’s, the two adjoining factories that produced her wares.

A chain of mergers eventually led to Wedgwood owning the Clarice Cliff name, and in the early 1990's they produced a range of reproductions of her highly sought 1930's Deco pieces. These were made to a high quality, and were produced in small numbers for sale to collectors who could not find (or perhaps could not afford) the most striking original pieces.

Clarice Cliff, Jugs, 1920's

Clarice Cliff Morning Set, Tennis Design, 1932

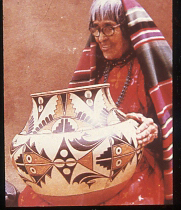

Maria was schooled only to the fourth grade. She was born in the San Ildefonso Pueblo, a Tewa-speaking community on the eastern bank of the Río Grande about 20 miles northwest of Santa Fe. Archaeologists believe that this village existed at that location since the 1300’s and was populated by descendants of those who once inhabited the canyons and cliffs of the Pajarito Plateau.

In 1880, a Smithsonian Institution collecting expedition headed by James Stevenson visited San Ildefonso, but Stevenson found very little pottery. He noticed that these people were spending most of their time in subsistence farming and almost totally abandoned the manufacture of pottery making. San Ildefonso had become increasingly depopulated since the arrival of the Spanish and then again when the United States government took over. By 1900, only 138 people lived in the pueblo.

Tin and enamel pots and pails replaced the pueblo’s ceramic tradition of finely painted black-on-cream ware. A cultural revival would soon be sparked by Martinez’s deep love for clay.

Maria’s husband Julian gathered, hauled, and purified her clay before she began mixing it. By 1919, Maria began producing the black-on-black pottery that would make her world-famous. Although black ware had been found at archaeological sites, the firing method that produced it had been lost. The couple began experiments to recreate the polychrome ware that was the most common form of pottery found on the plateau. They revived a unique Tewa way of firing at zero oxidation that had gone out of existence. At a certain point in the firing they smothered the pot with cow dung and let it bake and smoke for several hours.

Maria demonstrated pottery making at the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904, where she sold her pots for 50 cents or a dollar. Today, her pots garner more than a quarter of a million dollars at auction. Maria also demonstrated her pottery making at the San Diego World's Fair in 1915. She received the Best of Show at the Century of Progress; Chicago World's Fair in 1933 and was invited to the White House by President Theodore Roosevelt. In 1939 she made her pottery at the San Francisco World's Fair. Her work was included in two European tours between 1955 and 1961.

MARIA MARTINEZ, 1887-1980

As we move forward in the discussion of women’s role in the ceramic field,

we recognize the legacy of Maria Martinez, who revitalized the lost art form

of Native American pottery making. Her work, born from an ancient tradition, exhibits the life of a people that once populated most of our country. Today, Maria and other Native American potter's work can be seen in museums worldwide.

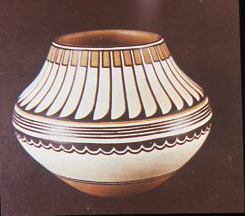

San Ildefonso 1935 Black on Black

Maria Martinez, 20th c

GERTURDE NATZLER, 1908-1871

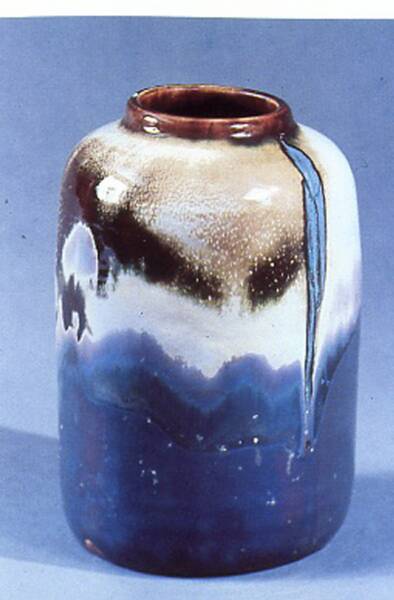

Gerturde Natzler was Viennese born. She and her husband, Otto, were Jewish émigrés that arrived in the US in 1938, and created one of the first successful working marriages in our ceramic culture. They set up their studio in Los Angeles, CA. Gertrude did all the throwing and Otto created the glazes and firing techniques. However, it was Gertrude’s exquisitely thin thrown vessels that made them famous. Their work can be seen in museums worldwide.

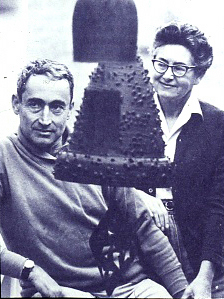

Otto and Gertrude Natzler

Footed Bowl, 1957

Bowl, 1948

As Art Potteries began to dwindle, the individual studio potter flourished. While mostly men were employed in the art departments of our country’s universities, many women were associated with art centers. However, both these institutions thrust the “Art and Craft Movement” into post war (WWII) America. While some potters chose to work with these establishments, others worked alone in private studios. Many of these individual potters had to rely upon patrons, spouses, and families to financially support them while they developed their studios and clientele. These potters sold their work through art centers, state and county fairs, small studio shows and local galleries. SOUND FAMILIAR? As the Art and Craft Movement escalated, more attention was focused upon the work of these studio potters, and pottery in general.

MARGUERITE WILDENHIEM

Marguerite Wildenhiem grew out of the post World War ll days, producing wheel thrown pottery that was soon to reflect the era of the Studio Potter. Her work typified much of the pottery of the 1950's, a world that was governed primarily by men. She immigrated to the United States in 1940, and wrote three influential books—Pottery: Form and Expression (1959), The Invisible Core: A Potter's Life and Thoughts (1973), and We Look and See: An Admirer Looks at the Indians (1979). She was an inspiration to potters of her day and the future.

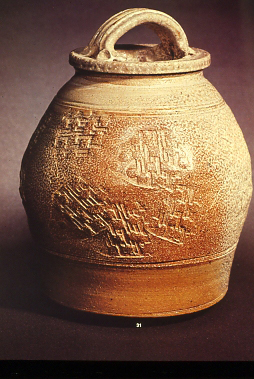

Cookie Jar, 1950's

Reduction Stoneware

Maija Grotell, Vivika Heino, and Karen Karnes produced strong stoneware pottery, emphasizing boldness of form and clarity of glaze color. Their work was representative of the finest ceramic work produced during the 1950’s and 1960’s, becoming a barometer of our country’s ensuing affair with the American studio potter.

MAIJA GROTELL, 1899-1973

Maija Grotell, was trained in painting, sculpture and design at The Ateneum, the Central School of Industrial Art in Finland, and then completed six years of graduate work in ceramics. Ceramic materials and teaching positions were very limited in Finland, so Maija decided to leave her country in 1927 and immigrate to the United States.

However, when Maija first came to the United States, there was not a great deal of opportunities for a career in ceramics. Even though American ceramics made some ground breaking achievements resulting from the glory of the Art Potteries, the greater part of American ceramics at this time was either industry or hobby based. The field of ceramics lacked an identity in the global history of art. Another important detail is that at this time, an understanding of the value of ceramics as an art form was not being considered. The conversation of Art Versus Craft would fill the art community’s dialogue for decades to come; the foundation for the development of this understanding was accomplished by the pioneer teachings of Maija. Soon the world began to realize the totality of the clay making processes. Ceramists needed to manage engineering competence for firing facilities, acquire knowledge in the chemical science of glaze making and develop throwing and hand building skills for a very unpredictable art medium-clay.

Maija’s first summer in the US was spent at the State College of Ceramics at Alfred, NY. She went on to NYC to teach at Union Settlement and the Henry Street Settlement, while she exhibited and sold her own artwork. From 1936-38 she became the first art instructor at the School of Ceramic Engineering at Rutgers University, NJ. Then in 1938 she joined the Cranbrook Academy of Art’s faculty in Michigan. There, she achieved her finest series of work. In her career she would win over twenty-five major exhibition awards and have her work purchased by over twenty-one museums.

This athletic woman was able to center fifty pounds of clay and produce perfectly centered vases. She spoke six languages, which probably facilitated her ability to communicate and teach with intelligence in language and aesthetics. Teaching was very important to Maija; she laid the foundation for students to develop a standard of excellence and creativity that would be unique to them. Her profound contribution to the education and advancement of ceramics in the United States is greatly appreciated to this day.

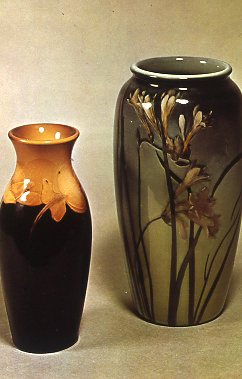

VIVIKA HEINO, 1910 – 1995

Vivika Heino studied under Glen Lukens at the University of Southern California and received her MFA at New York State College of Ceramics, Alfred, New York. She became an outstanding teacher. Otto, her student became her husband. Vivika and Otto displayed an openness and accessibility in both their way of life and their work. She readily shared with others her vast knowledge of clays, glazes, and technical knowledge of firing kilns. Vivika's work had a delicate aspect in porcelain and stoneware, but her greatest gifts were the glazes. The rich colors and variety and clays Vivika and Otto formulated can be found in every ceramic laboratory and have been shared with many people through books and magazines.

Vivika participated in over 200 national and international exhibits, and was awarded many distinctions and recognitions. In 1978, Vivika was appointed to the Apprentice Fellowship Advisory Panel of the National Endowment for the Arts. In 1991, Vivika was honored as Trustee Emeritus for the American Crafts Council in New York. Vivika and Otto, originally from the east coast, settled in California and made their home in the east end of Ojai in a house formerly owned by Beatrice Wood.

Vivika Heino, Bowl, 1980

LUCY RIE, 1902-1995

American women were not the only ones creating influential ceramics. As we cross over the pond, we land in England, home of the male dominated Leach, Cardew and Casson dynasties. Out of this mix came Lucy Rie. Lucy has been described as one of the most important figures in 20th century British art and was made a Dame in 1991.

Lucy Rie (Gomperz) was born in Vienna, a Jewish émigré who safely sought refuge in England. In a career, which spanned almost 70 years, Lucie gave ceramics a new identity. In 1937 she won a silver medal at the Paris International Exhibition and by the Second World War she was well known in Europe. Functional tableware with delicate sgraffitto decoration is typical of Lucy’s style. She taught at the Camberwell School of Art and in 1968 won an OBE. Lucy ‘s work is held in many private collections and can be seen at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

Lucy developed a unique body of work that emanated from an alteration of classical forms. She brought the bottle form into the 20th century. Her elongated narrow necks with unconventionally wide undulating rims gave testament to a masterful throwing ability. Her beautiful bowls with daringly narrow feet and wide rims set a standard for future generations of potters. Her gorgeous glazes evolved from exotic lusters to golden yellows, and made her the Grand Dame of English ceramics, and an inspiration to potters worldwide.

Lucy Rie 1965

Lucy Rie 1967

Lucy Rie 1975

THE FOLLOWING WOMEN HAVE MADE MAJOR CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE CERAMICS FIELD; THEIR WORK HAS GENERATED EXAMINATION, ANALYSIS AND RESPECT. WHILE MOST OF THEM ARE STILL LIVING AND PRODUCING SUBSTANTIAL WORK, I HAVE CHOSEN TO PRESENT EXAMPLES OF THEIR ARTWORK THAT ILLUSTRATE THEIR PIONEERING EMERGENCE INTO THE CERAMIC SCENE, OPENING THE DOORS TO WOMEN CERAMISTS WORLDWIDE.

KAREN KARNES, b. 1925

Karen Karnes was a dominant force in the beginning of the crafts movement during the early 1950's. She has influenced generations of potters and is widely recognized as a ceramic educator, although she never taught through traditional college programs.

Karen's parents were Jewish immigrant garment workers from Russia and Poland, and raised their daughter in a housing project in Bronx, NY. She studied at Brooklyn College's Art Department where she developed artistically, leaning towards the proponents of the Bauhaus. Karen did not work with clay until she married David Weinrib. He brought clay home for her and thus changed the direction of her life. Karen soon began earning her living as a studio potter.

Karen was a Potter in Residence, teaching at Black Mountain College. She then taught at the Penland School of Crafts and Haystack. She left teaching in the 1960’s, becoming an influential participant in Stony Point, N.Y., an artist community founded on communal living and art production. It was there that she lived and worked for 25 years, establishing herself as one of the leading ceramists in America.

A great tragedy occurred for Karen when a fire destroyed her house and studio in l998. From the love of potters all over country, financial support flowed in which enabled her to rebuild her life and studio. She has worked in clay for over 60 years, and continues to produce beautiful artwork in her Vermont studio. Her work is in major collections throughout the world.

Split Casserole, wood Fired, 1985

Lidded Jar, 1979

Sculpture Group, Recent Work, 2000's

RUTH DUCKWORTH, 1919-2009

Ruth Duckworth was born in Hamburg, Germany. Banned from art school in Germany, Duckworth fled to England. She carved tombstones for a living, and worked in a munitions factory making bullets during the war. There she polished the dies in which the bullets were cast, always working with the bullet shape. That form became a major element of her work.

In 1964 Duckworth moved to America when the University of Chicago offered her a job. There, she remained for thirteen years, gaining her first commission, "Earth, Water and Sky," a mural for the Geophysics building. Her murals and sculptures were created in her studio, an old pickle factory on the north side of Chicago. There, she worked every day, making her small models in clay. Most of her sculptures are abstract, shaped in stone, porcelain and bronze. A 16-foot-high sculpture at Northeastern Illinois University is one of a number of her oversized installations. Another one, called "Clouds over Lake Michigan," resides in the lobby of the Chicago Board Options Exchange.

Ruth enjoyed a successful career spanning six decades. She created a body of work that is exceptional in breadth, size and beauty. Her porcelain cups sell for thousands of dollars, and larger works go for hundreds of thousands. Her vessels are reminiscent of modernist sculptures, yet boldly contemporary. But what make Ruth singular are her wall murals. This small woman created work that fills great spaces in content and size. I think her wall sculptures inspire me more than any other ceramic artist I know.

Ruth Duckworth, 1979

Enclosed Forms, 1950'st.

Wall Piece, Untitled,

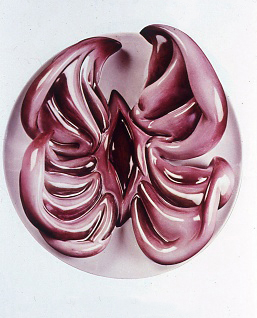

JUDY CHICAGO, b. 1939

During the 1970’s, the art world produced a great deal of feminist based art, reflecting the powerful voices emanating from the Women’s Liberation Movement, commonly referred to as Women’s Lib. This movement sought to define women’s place in history through research and communication among the populace by people in all areas of life- art, music, science, literature, politics, medicine, etc. One of the most prolific and vocal of the feminist artists was Judy Chicago, born Judy Cohen. Originally a painter, Chicago went to auto body school, boat building school and apprenticed a pyrotechnician, to prove her abilities in the very macho based pop art world of Los Angeles of the early 1960’s.

Judy began producing metal and fiberglass sculptures, displaying explicit sexual and feminist imagery. She began teaching at the California Institute for the Arts becoming a leader in the Feminist Art Program. Judy was determined to bring female themes and images to the art world that was dominated by male artists and male historians. She continued to paint, sculpt, produce craftwork and write; most of her themes continue to revolve around Feminism.

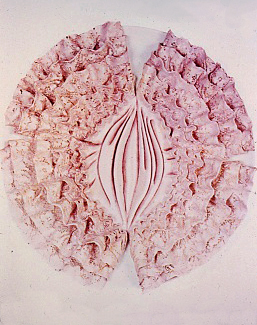

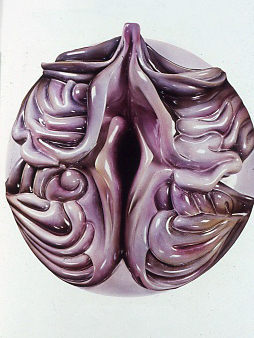

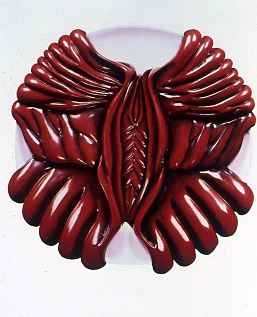

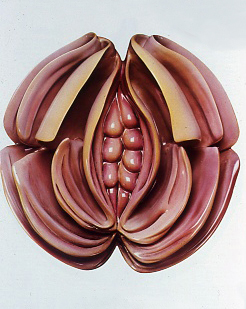

Judy's groundbreaking masterpiece, “The Dinner Party”, 1979, was first housed at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York. It was a triangular table that contained 39 place settings. Each highly sculpted and painted porcelain plate was a visual interpretation of a notable woman in history who advanced women’s status in the world through her unique contribution or work. The entire table was positioned on a floor of 999 tiles, each exhibiting a name of a woman whose life’s work contributed to the advancement of women. Recently, over thirty years after its tour around the country, the “Dinner Party” has been on exhibit again.

Emily Dickinson, Writer, 1830-1886

Georgia O'Keefe, Painter, 1887-1986

Margaret Sanger, Birth Control Activist

1879-1966.

Virginia Woolf, Writer,1882-1941

Sojourner Truth, Slave, Abolitionist,

1797-1883

Susan B. Anthony, Suffragette

1820-1906

VIOLA FREY, 1933-2004

Oakland, CA Sculptor Viola Fray, a pioneer in California ceramic sculpture, was known for her colossal clay figures. She was born in Lodi, California. Viola received her BFA in 1956 from the California College of Arts and Crafts (now California College of the Arts), and was a student of Richard Diebenkorn. She earned her MFA in 1958 from Tulane University, studying briefly with Mark Rothko. After spending two years on the East Coast, working at the Clay Art Center in Port Chester, N.Y. and in the business office at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, she returned to California in 1960. Along with Peter Voulkos and Robert Arneson, she became one of the most influential Bay Area ceramists, teaching for more than 30 years at the California College of Arts and Crafts and exhibiting widely.

Using thick, gaudy glazes or china paints associated with hobbyists, Viola developed a deliberately unrefined style that led to her being linked with Funk art. In the late 1970s, she began making the giant statues for which she became best known. She expressed these stiff figures, some 11 fee high, with wild, trancelike expressions that commanded a great psychological space.

In 1981, the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento organized a traveling exhibition, which included her work, and in 1984 New York's Whitney Museum of American Art gave her a solo show. Four large figure groups were shown at the Boise Art Museum in 2001-02. At her death, Viola was preparing for an exhibition at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville, the Cameron Art Museum in Wilmington, N.C. and the Nancy Hoffman Gallery in New York. Viola Frey died in 2004 at the age of 70.

Self Portrait,1979-80, 65" h.

Double Grandmother, 1979, 64"h..

Greek Figure, 1979, earthenware

BEATRICE WOOD, 1893- 1998

Beatrice Wood was an important contemporary artist, craftsperson and writer. Her life spanned the 20th century and included many of the people that shaped it. The spirit of Dadaism, the impact of Modernism, and her embrace of Eastern philosophy were all apparent in her work.

Beatrice was born in San Francisco to wealthy, socially conscious parents, a lifestyle from which she tried to disenfranchise herself. At 19 she studied painting in France, then theater. When World War 1 erupted she moved back to the United States and continued her acting career. In NY, she met Marcel Duchamp, who brought the DADA art movement to her. She remained good friends with Duchamp until his death. In NY she exhibited her paintings that were photographed by Stieglitz. This prompted her to write about her work in the avant-garde journal The Blind Man, which went on to become an icon of modern art. In 1918 she met Dr. Annie Besant of the Theosophical Society and the Indian sage Jiddu Krishnamurti, who were to remain vital to Beatrice for the rest of her life.

In 1933, in Ojai California, Beatrice enrolled in a ceramic course at Hollywood High School. She studied glaze chemistry while learning to throw pots. In the late 1930s, Beatrice studied ceramics with Glen Lukens, and then worked with her most important mentors – Gertrud and Otto Natzler. They took her on as a student, sharing their techniques and glaze secrets.

In 1947, Beatrice built her home in Ojai. Her work had been included in exhibitions at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. She received orders from major department stores including Neiman Marcus, Gumps and Marshall Fields. Her new home in Ojai was located across the street from Krishnamurti and she began her life among the artists, actors and others in search of alternative lifestyles. She began a lifelong friendship with Vivika and Otto Heino, who helped her with throwing and luster glazes. Beatrice started teaching ceramics for the Happy Valley School (now called the Besant Hill School) while operating her studio and showroom. She was in her late eighties when her first book, The Angel Who Wore Black Tights, was published. A few years later, her autobiography, I Shock Myself, was published, followed by Pinching Spaniards and 33rd Wife of a Maharajah: A Love Affair in India. Beatrice Wood had become a writer.

Beatrice Wood embraced a romantic life that combined the wisdom of the East, positive thinking, a strong work ethic, and a great sense of humor. Her personal philosophy served her well, as she continued working in her studio to the age of 104.

Luster Vessel, 1978

Bottle, 1979

Luster Teapot, 1975, 12"h

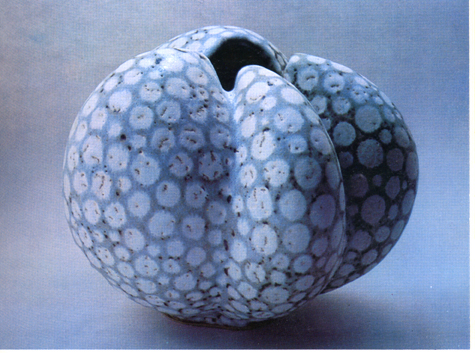

TOSHIKO TAKAEZU, 1929-2011

Toshiko Takaezu was born in Hawaii of Japanese decent, and has been working in clay for over forty years. She moved from producing functional vessels to abstract sculptural forms. Over the years she has merged the aesthetics of the East and the West, as well as her love of the natural world. Throughout her career, Toshiko has focused on the enclosed vessel, which has become a symbol of her work. Her earlier pieces were almost exclusively wheel-thrown, but she began envisioning larger forms. With these forms she incorporated hand-building techniques that allowed her to build larger vessels and stray from the restrictions of the wheel. The simple structures are united by form but gain individual character through her painterly surface decoration. Toshiko’s spontaneous approach to glazing occurs as she walks around the vessel freely applying glaze through pouring and painting.

Toshiko ‘s love of teaching has been a great contribution to the ceramic field. Her passion for clay is infectious, and she has continually shared this enthusiasm. While teaching at Princeton University for 23 years and presenting workshops throughout the world, she always had time for generations of apprentices. Among the many awards she has achieved, her greatest achievements were the Hawaii Living Treasure Award and an honorary doctorate degree from the University of Princeton. She has been an inspiration to many through her work and life’s contributions.

Gaea Moon Pots, 1979, 30"-33" d.

Uariramba, 1970.

Toshilo Takaezu

Light, 36" h. 1970

FRANCES SIMCHES, 1920-1976

Fran Simches made a vital contribution to our country's ceramic repertoire. She was a passionate teacher and shared this enthusiasm with her students. She created a body of work that left an enduring impression on those who knew her. Her work touched all areas of ceramics, from utilitarian ware to fine vessel making. Unfortunately, her life was shortened by an insurmountable battle with cancer.

Fran was born Frances Goldsmith, in Jackson, Michigan. She became involved in pottery "through the back door" (as she termed it) during World War II in New York City. At that time there were no men around and the potteries were luring women as apprentices. Upon leaving a Spanish teaching position in Michigan in 1945, Fran went to New York City where she met a couple that were involved in pottery. Being fascinated with the medium, she took on a two-year apprenticeship and began studying at night at New York University. She was hired as a student assistant, and upon receiving her Master's Degree in Ceramics and Education from New York University, she became an instructor there from 1951-1954. She also taught part-time at the Greenwich House Potters in New York City from 1948-1955. She pursued postgraduate work at Alfred University until 1965. It was during a summer course at NYU, that Fran met her husband, Ray, a student in her pottery class.

The couple moved to upstate New York where Fran took a position teaching ceramics at Russell Sage College, in Troy, NY during 1958-1959, while maintaining a studio at home. She felt it was essential to live with her work, and as the years progressed, her work became large and sculptural, requiring constant attention.

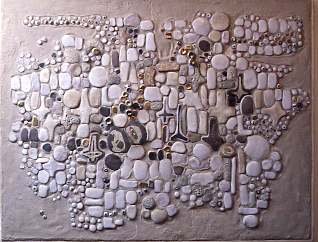

Initially, Fran made production ware such as casseroles, vases, bowls and teapots. Her work was sold through such prestigious concerns as George Jensens and Rabun Studios in New York City. She began working with mosaic tiles and produced her "White on White" wall panel, which created much acclaim. She received several awards for this piece. In particular, she received one from the Designer Craftsmen USA show held at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in 1960. The American Craftsmen's Council sponsored this show as a result of a debate over art versus utility. Fran's panel won an award certificate.

She became nationally recognized and was invited to submit work to the United States Information Agency Craft Show in 1960, which traveled for two years throughout the United States and Europe. Again, she won an award for her panel in this show and was recognized by the Technical Advisory Committee, which stated that her work was "particularly representative of the best American ceramic mosaics."

At this time, Fran and Ray purchased an old church in Rensselaerville, NY. This would be their home and her last private studio. One entire side of Fran's bedroom garret was enclosed in glass, overlooking her studio and gas kiln. The home was filled with an eclectic array of ceramic objects and Abstract Expressionist art.

In 1961, Fran began her final teaching position at the State University of New York at Albany as Assistant Professor of Art and worked there until 1974, when she became ill. It was there that I began my friendship with her, my only teacher.

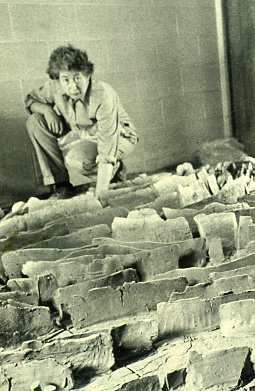

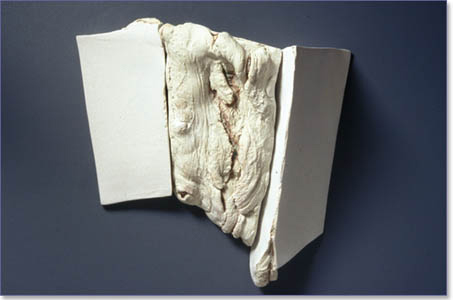

Fran constructed huge slab forms assembled with plywood supports, developing a technique that enabled her to make forms of unlimited size yet maintain the crispness of freshly rolled slabs of clay. This technique utilized plywood boards as a frame, which encased the slabs while the firming process progressed. She retained the rigidity of the slab and juxtaposed them with covers that were organic and plastic. This merging of two contrasting forms became representative of her body of work. Refer to Ceramics Monthly magazine, October 1972, pp.30-33.

The strength and vitality of her boxes appeared to be her ultimate public gift; her final work became private as she continued to work while the cancer ravaged on. She became involved with the intricacies of paper-thin porcelain slabs. She worked with thinly rolled porcelain slabs, wrapped around delicately sewn foam rubber forms. She wedged colored oxides into a white body, creating a marbled effect. Some of the pieces were electroplated with heavy deposits of metals, a technique that gave her the appearance of a mad scientist, rather than an artist. I think these last pieces were some of her finest work.

Box, 1971

Fran Simches died in 1975. I was one of those very fortunate people who worked with her and knew her well. Her teaching career of thirty years left an indelible mark on the world of ceramics. Students from Michigan to New York will always remember this remarkable woman. Fran Simches will not be forgotten-she was one of the great pioneers of Ceramic Art in our country..

Chest, 1972

White on White, 1959

PAULA WINOKUR, b.1935

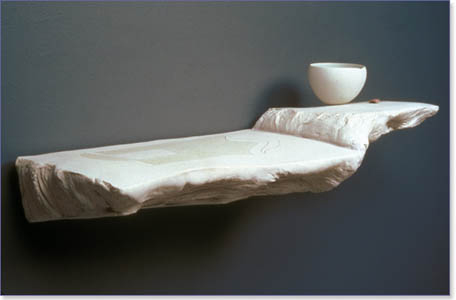

Paula Winokur was born, grew up and worked in Horsham, Pennsylvania. Since the late 1960s, she lived there with her ceramic artist husband Robert Winokur. Her early works were functional, vessel forms, mostly thrown in stoneware. In the early 1970's Paula moved to porcelain, which has become her signature material. While porcelain has traditionally been associated with small and fragile objects, Paula was drawn to exploring the possibilities of large scale and since the early 1980's, she has created large sculptural works for the wall, floor, and pedestal.

Paula has received international acclaim for her contributions to the field of ceramics. Her work can be found in permanent collections across the United States as well as notable collections abroad. In 1986 she was distinguished by her inclusion in "Craft Today: Poetry of the Physical," the inaugural exhibition for the American Craft Museum, now the Museum of Arts and Design in New York. A graduate of the Tyler School of Art, Paula has been recognized with two fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, in 1976 and 1988. She is also the recipient of numerous grants, including two from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts. In 2002 she was appointed a fellow with the American Crafts Council. Paula served as professor of ceramics at Arcadia University, formerly Beaver College from 1973 until her retirement in 2003. She has been the subject of numerous critical and informative articles on contemporary ceramics. Her work is included in important private, corporate and museum collections including the Mint Museum, the American Craft Museum and the Renwick Gallery.

.

Fireplace, 1985

Glaciated Rift V, 1999, Porcelain

Repetitions, Wasp Ledges, 2003

Porcelain handbuilt and thrown

White Canyon Ledge, 2000, 35" w x 9"h x 6" d

Porcelain handbuilt and thrown

MARILYN LEVINE, 1935-2005

Marilyn Levine was a Canadian-born ceramic artist, who originally studied art and taught sculpture at the University Of Regina in the 1960s and early 1970s. She made her fame in the ceramic field for her trompe l’oeil images of ceramic leather objects, such as handbags, garments, briefcases and boots. She exhibited in galleries across the United States and Canada as well as Europe and Asia.

Marilyn was born in 1935 in Medicine Hat, Alberta. She moved to Edmonton in the 1950s to attend the University of Alberta, where she graduated with a master’s degree in chemistry. It was Marilyn’s parents that influenced her in art and Marilyn began painting. Unable to find employment in her field of chemistry, Marilyn enrolled in drawing, painting, art history and pottery courses at the University Of Saskatchewan’s Regina Campus. There, she studied art for several years while periodically teaching chemistry at Campion College. Finally, she resigned from teaching chemistry in 1964 and enrolled in the School of Art at the Regina Campus. Marilyn began showing her work in Saskatchewan and across Canada, while continuing to teach ceramics classes in Regina. In 1969 she moved to the United States to enter the Graduate Sculpture Program at the University of California, Berkeley. It was there at Berkley that she became intrigued with inanimate objects and the super realistic rendering of leather objects in clay. In 1973 she became an assistant professor of sculpture at the University of Utah, moving back to the US permanently.

Marilyn continued creating her unique leather objects until her death in 2005. Marilyn Levine was a forerunner of the very contemporary exploration of ceramic as “object d’ arte”, a major factor in American ceramics. She helped position ceramics as art and not solely a functional decorative item. Her contribution is vast to the promotion of the ceramic field.

Hanna's Bag, 1985, 19 1/2" h

Spot's Suitcase, 1985

CYNTHIA BRINGLE

Cynthia Bringle is known for both her functional pottery and for her enthusiastic teaching and mentoring. She has had a long career at Penland, North Carolina, creating work that reflects the culture and history of the southern highlands. Cynthia began as a painter, and continues to paint as well as decorate her work in a painterly fashion, creating what she terms as ceramic “Wall Paintings”

Cynthia began her career at the Memphis Academy of Art where she first took a short course in clay. She then took courses at Haystack School in Maine. Upon meeting Dan Rhodes in Haystack, he helped her become accepted at Alfred University. At Alfred, she studied with both Robert Turner and Ted Randall. It was then that she returned to North Carolina and began teaching at Penland School, where she helped develop the ceramics program. She now lives permanently in Penland.

At Penland she built a gas car kiln, a wood-fired kiln, and a raku kiln. She enjoys working with the Anagama kilns, creating work that utilizes the resulting ash deposits of the firing process. Cynthia Bringle exemplifies the best of American functional and non-functional art pottery.

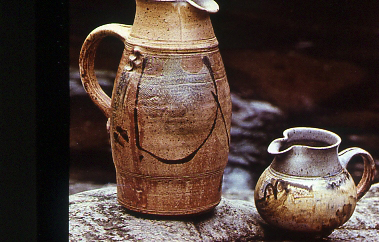

Two Pitchers, 1972

Salt Jug, 1970's

PATTI WARASHINA, b. 1940

Patti Warashina was born in Spokane, Washington. Her father emigrated from Japan and married her mother who was Japanese American. Patti went to the university of Washington where she received both her BA and MFA. While in school there she had the opportunity to study with Robert Sperry, Rudy Autio and Shoji Hamada. Her first solo exhibit was in 1962. She married Fred Bauer, and from 1964-1970 she exhibited as Patti Bauer.

Patti became enamored with the California funk art, surrealism and experimental sculpture that was being developed in California in the 1960’s. Her work developed into satire, utilizing humor and dream like figures. She works in low fire with polychrome ceramic materials. She became famous during her tenure at the University of Washington’s School of Art in the late 1970’s.

Patti has won numerous awards and received several grants, including the National Endowment for the Arts in 1975 and 1986. Her teaching career has spanned over 30 years, including positions at the University of Wisconsin, Eastern Michigan University, Cornish Art Academy in Seattle as well as the University of Washington, where she has taught for the past 25 years. Her work is included in many museums throughout the world, including the American Craft Museum in NYC, the Los Angeles County Art Museum, the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Renwick Gallery. Since her marriage to Robert Sperry in 1976, she has used her name, Patti Warashina. Patti currently lives in Seattle, Washington, and continues to create ceramic sculpture.

Warashina, 1976

Warashina, Heart, 1979

MARY FRANK, b.1933

The artist Mary Frank initially established her reputation through her paintings, drawings and prints. But during the 1980’s, she began working in clay and established herself as a figurative sculptor. As she moved from paint

to ceramic sculpture, and then back again to oil painting, she continued to maintain an interest in the moving line emphasizing tonality and color. In her paintings, her colors connote an expressionistic attitude that is similar to her slab constructions of the human form. Her paintings are vivid in color, while her sculptures exhibit a monochromatic orange-red surface quality that enhances the stark, abstraction of form. Whatever medium she chooses to work in, Mary’s art has been consistently representative of imagery in horses, shrouded figures, hands, birds and the female figure. Her expressionistic work evokes various states of feeling and emotion.

Mary has worked and lectured at the New School for Social Research, Bard College, Smith College and Harvard University. She has also illustrated several books. Her art is included in many museum holdings such as The Museum of Modern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Whitney Museum of American Art, The Hirschorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, The Art Institute of Chicago and the Library of Congress. She has received two Guggenheim awards, and was elected into the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters in 1984. When Mary began working in clay, she helped elevate the field of ceramics; she is viewed as a “fine artist”. Mary traditionally paints and sculpts, utilizing clay as a final medium, not just a maquette. Mary has shown the world the enduring quality of ceramics as a vital form of sculpture.

I have been following Mary Frank's work for over thirty years and believe her sculpture to be some of the finest of the 20th century.

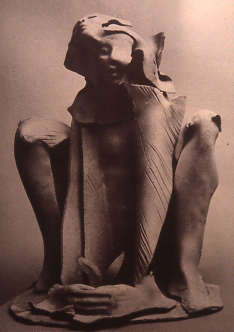

Crouching Woman With Two Faces, 1981, slabs, 29"x24"x16"

USA Lover, 1977, slabs, 23"x 44"x 25"

Three Dancers, 1981, slabs, 29" x 34" x 25"

MARY ROGERS, b.1929

Mary Rogers, was born in Belper, England. She studied graphic design at Watford School of Design, calligraphy at St. Martin's School of Art in London and ceramics at the Loughborough School of Art. She worked for several years as a calligrapher and graphic designer before establishing her own workshop in Loughborough. Mary worked from this studio for the bulk of her career, but then finally worked out of her studio near Falmouth, Cornwall till the end of her career. Mary’s early work is comprised of large coiled stoneware pots inspired by nature. However, in the early 1970s, Mary garnered her fame by making small porcelain bowls fashioned after leaves, flowers, twigs, pods, and other natural forms. She began working on small, delicate porcelain forms and some larger stoneware pieces that reflected natural objects and forms found in nature. Her beautiful organic pieces became an inspiration to ceramists who sought out her hand built forms.

Mary Rogers retired from producing ceramics in the 1990s having created a body of precious small-scale pieces, mainly in porcelain. Her work has been very widely collected by museums and of contemporary ceramics.

Billowing Form, 1983

Pod Form, 1984

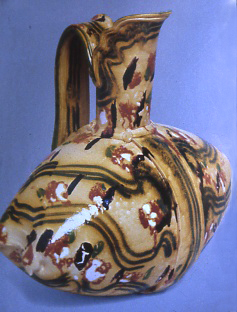

BETTY WOODMAN, b. 1930

American-born artist Betty Woodman is internationally viewed as one of the most important ceramic artists working today. Her contribution to contemporary art has been in the interrelationship of her work between ceramics, sculpture, and painting. Her evocative use of color and form, emanating from historical references, has evolved into an exuberant and captivating body of work.

Her work employs many forms, from fragmented wall vases to pillow pitchers. She has traveled extensively, finding inspiration in cultures around the world. Betty developed a glaze palette reminiscent of Tang dynasty China and Japanese Oribe ware. Her colors initially bled into one another, exemplifying the beautiful greens, yellows and browns of Asian and Mid Eastern influences. Alongside her rich color scheme, her forms resonate with the vitality of early Greek vases.

Betty has merged the traditions of fine art and craft, employing elements from the rich heritage of each in a unique and personal style. She uses the motif of the vase and the vessel repeatedly, each one exhibiting her exploration of formal and painterly traditions. While Betty’s work has historical references, they also convey the attitude of Modernist art, to which they owe their visual interest.

Betty Woodman lives and works in New York City and Antella, Italy. Her work has been shown around the world in exhibitions in France, Italy, Holland and Japan. In June 2006 Betty Woodman earned the distinction of being the first ceramist to have a retrospective of her work at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City

Since 1985, Woodman has been producing monotypes, woodcuts and lithographs with the same enthusiasm as her ceramic work. Betty’s two-dimensional metaphors are collections of collages that create images of pottery gathered in interiors, similar in form as she cuts and assembles her ceramic pots. Her prints are references to the rich history of ceramics around the world, with monotypes entitled "Oribe Tray", "Etruscan Pot" and "Iznik". These paper representations harmoniously coexist with her ceramic art work.

Betty's work is in the collections of many museums, such as The Museum of Modern Art, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, The Brooklyn Museum, The Metropolitan Museum, The Smithsonian Institute and The Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Earthenware, 1977d text.

Persian Pillow Pitcher, 1980

His and Her Vases, 2004, earthenware, epoxy resins, laquer and paint, 29" x 72" x 9"

His and Her Vases, opposite side, 2004, earthenware, epoxy resins, laquer and paint, 29" x 72" x 9"

ALEV EBUZZIYA SIESBYE, b. 1938

Alev Ebuzziya Siesbye, born in Istanbul, turkey, studied sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts, Istanbul and from 1956-1958 worked at Fureya’s Ceramic Workshop, Istanbul. She spent two years working in a ceramic factory in Germany, then returned home to Turkey and worked at the Eczacibasi Ceramic Factories Art Workshop. During 1963 to 1968 she went to Denmark and worked in the Royal Copenhagen Factory. Her work is coil built, but is so refined it has the appearance of thrown work. She has been awarded many international prizes and her work is in over thirty museums and collections, such as the Danish Museum of Decorative Art, the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Musee Bellerive, Switzerland and the Museum of Decorative Arts, Belgium.

Clearly, the Middle East is in a state of tremendous turmoil; they have encountered much difficulty in the past few decades in supporting the arts. However, it must be remembered that a rich history in ceramics spans the centuries of this region.

At one time this region contributed some of the most beautiful artwork in the world. As we see in Turkish ceramist Alev Ebuzziya’s bowls, the Middle East is finding their way towards the 21st century in ceramic art.

She wrote a best selling self-help book on china painting in two weeks. In 1877 she began experimenting with this technique and in three months discovered the secrets to under glaze painting, a feat that took the Europeans centuries. She became the first American to work in under the glaze china painting.

In 1879 she founded the first woman's pottery club in America, the Cincinnati Pottery Club. In 1895, she patented a technique for inlay decoration in pottery. In 1898 she built a kiln in her back yard and became the first American to work in studio porcelain, the most difficult of all clays. This phenomenal woman came out of early Americana, yet traversed the decades and initiated the stepping-stones for future studio potters.

Maija Grotell Bowl 1956

PALEV EBUZZIYA SIESBYE,Turkey, 1984

PALEV EBUZZIYA SIESBYE,Turkey, 1986t.

© 2008 Jayne E. Shatz