JAYNE SHATZ POTTERY

PhD-Prehistoric Ceramics

MA- Pottery and Sculpture

BA - Art History

© 2014 Jayne E. Shatz

NATIVE AMERICAN POTTERS OF THE SOUTHWEST

THE STORY OF OUR COUNTRY'S EARLY POTTERS

The great Ice Age occurred between 110,000 and 12,000 years ago, and then the glaciers melted away in 11,000 BPE. A period of particular artistic fervor flourished with the Paleolithic people who roamed the Earth from 40,000 to 12,000 BPE.

During that time, these Cro-Magnons developed the beginnings of very sophisticated art forms;

the first sculptures were produced around 32,000 BPE and the first kiln site was operational in 27,000 BPE. The brilliant cave paintings were executed around 15,000 BPE.

While clay sculpture was being fired in a kiln in 27,000 BPE, until recently we had no evidence of pottery before 12,000 BPE; some of our earliest known ceramics were the magnificent vessels of the Japanese Jomon potters. However, ten years ago a fantastic discovery was made at The Xianrendong Cave in China, which dates back to 18,000 BPE. Excavations unearthed functional pottery which was created for foodstuffs, presenting us with the first cookware dating 20,000 years ago. For more detailed information on prehistoric ceramics go to my lecture at

http://www.jayneshatzpottery.com/ICEAGE-CERAMICS.html.

This new discovery affords us a greater vision of pottery’s history, and so we come to ask more questions. Who laid the seedlings of America’s artistic venture, specifically my country’s ceramic heritage? We know that the earliest settlers in America’s lands originally migrated from the North, either across the Bering strait or by way of the Aleutian Islands. They come down the West coast (now California), into the Missouri and Mississippi regions. Slowly they traveled southward seeking warmth and then eastward across the central plains into the New York and Florida areas. These ancient people were descendants of the East Asian race, with warm brown skin, little body hair and broad faces outlined with straight black hair.

We know that pottery was produced in the areas of settlement where agriculture and then masonry was practiced. The earlier hunter gatherers were people who mostly hunted or fished for their diet. They had little need for storage vessels, being nomadic; they were constantly traveling to where there was good hunting. They began producing pottery when they became more agrarian and settled down in communities. They produced coil built pottery, eventually decorating them with incised symbolic patterns. These pots were made by rotating the forms either between their legs while sitting on the ground, or resting the pot on a stable form. Later, the ware was lively painted in various colored clay slips. Some items made from clay besides heating and storage vessels were oil lamps (Eskimo), figurines, burial urns for cremations and pipes.

There is evidence of people living in the area that we know as the American Southwest in 1500 BPE, with some evidence of pottery making. When we examine our Southwest Native Americans, we designate their prehistoric period to work produced during this time, and pottery was initially produced in Mexico and the Meso Americas. These early people formed civilizations long before the Europeans explored the New World, notably the explorations of Coronado in 1540. Around 700 PE, three large groups, the Anasazi, Hohokam, and Mogollon developed their cultures.

There are earlier traces of pottery making in the Southeastern parts of America from the Savannah River in Georgia and South Carolina dating back to 2888 BPE, and some from northern Florida dating from 2460 BPE. However, something unique occurred in the Southwest; great pottery making centers developed in a collected group of settlements, resulting from trade and communications with neighboring tribes. These Indians developed pottery making skills to a highly sophisticated level. When we examine our Native American pottery, we refer to much of the ware produced in the Southwest Pueblos, Tribes and Reservations. Therefore, I have chosen to present this lecture on the history and development of our Native American pottery from this particular area.

DESIGNATION OF ANCIENT ERAS

Archaic-Early Basketmaker Era 7000-1500 BPE

7000-1500 BPE

Early Basketmaker ll Era 1500 BPE-50 PE

1500 BPE-50 PE

Late Basketmaker ll Era 50-500 PE

50-500 PE

Basketmaker lll Era 500-750 PE

500-750 PE

Pueblo l Era 750-900 PE

750-900 PE

Pueblo ll Era 900-1150 PE

900-1150 PE

Pueblo lll Era 1150-1350 PE

1150-1350 PE

Pueblo lV Era 1350-1600 PE

1350-1600 PE

Pueblo V Era 1600-Present

1600-Present

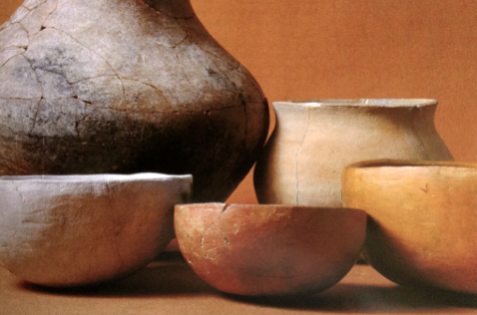

LATE BASKET MAKER II PERIOD

PUEBLO 1

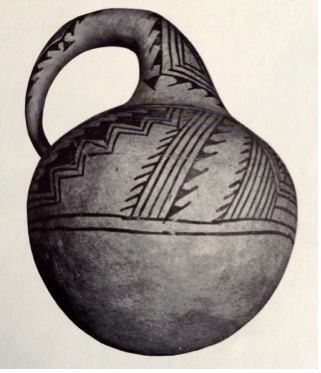

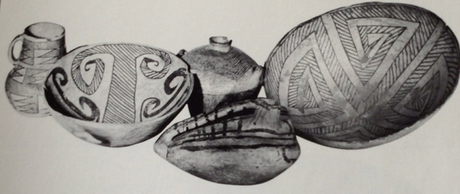

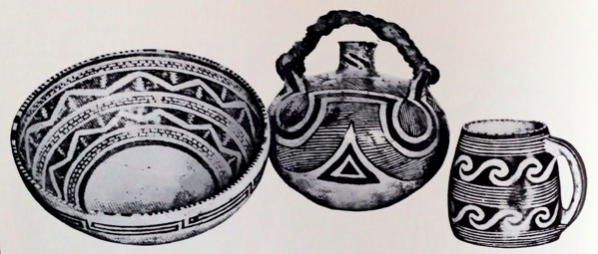

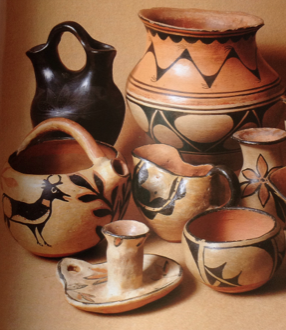

The pottery evolved during The Basket Maker II period as simple bowl forms, then expanded during Pueblo l with enclosed forms in the shape of gourds exhibiting elaborate black line figure painting. As pottery continued maturing into the Pueblo ll era, the work became more sophisticated with open bowl forms and closed containers reflecting the needs of agrarian societies which emphasized storage needs.

Pottery grew in complexity as the cultures progressed into the Pueblo lll era, using black sip as the background with white areas for design, as well as the traditional white background with black design. Color emerged in the pottery with the addition of bright orange red earthen slips and clay bodies and a more bold abstract style. Of the earliest developing Basket Maker cultures, the Anasazi were the most prolific potters, leaving behind a great legacy of work. However, they disappeared, and no one really knows what happened to the them. Toward the end of their cultural reign, the Anasazi moved into cliff houses with no apparent violent end to their story. What we do know is that after the 1300's they experienced severe draughts and poor soil management, and they began abandoning their homes. They had a large population that slowly dispersed into the Rio Grande and Hopi mesas. Many believe the Hopi are the true descendants of the Anasazi.

COLORED ANASAZI BOWL AND JUG 900-1000 PE

PRIMITIVE FIRING TECHNIQUES

There are two basic pit firing techniques developed by prehistoric potters which are still employed today by contemporary traditional potters of the Southwest.

They are shallow pits with the floor covered in a layer of fuel; this fuel could be wood, branches, bones, corncobs, etc.- any carbon, organic material. Today, traditional potters use mostly wood and sheep dung. When the fuel is smoldering, vessels are set down on shards, and surrounded by more shards for protection against falling debris. Pots must be made with well tempered, or grogged material for strength and to help prevent cracking during firing. Grog is made from previously fired shards that are ground up and added to the clay body. On top of the protective shards, more fuel is added to the pit, and then fired to desired temperatures. Present day potters use metal racks to set their pots on and protective sheet metal to cover them during the firing. Upon cool down, dirt and dung are added to the smoldering fire, developing the rich black colors in this reduction atmosphere. For those potters who worked in bright red and orange slip painted clay bodies, they fired their ware in open pits, with no covering. This provides the firing an oxidized atmosphere, developing the bright red coloring.

The Ancient/Prehistoric pueblos (communities of the Southwest Native Americans) with overlapping cultures:

MOGOLLON, 1-1450 PE

The Mogollon, (mug-ee-on), were the first documented potters in the Southwest regions. They were the first to grow corn and squash, and the first to irrigate, which led to a very successful agrarian society. These agrarian people needed storage vessels for their food items. They initially had mud lined baskets in the Early Basket Maker ll era; later on they developed a more permanent pottery with fired ware. They fired their coil built pottery upside down to create a blurred black smokey inner surface to the ware. They employed carved textural designs as well as simple painted geometric lines. They buried their dead, which enabled archaeologists to discover shards and pottery. Like many ancient civilizations, they slowly merged with other clans, increasing their lands and strengthening the variety in their culture. The Mogollon became related to the Hohokam, Saledo, Sinagua and eventually the Mimbres societies.

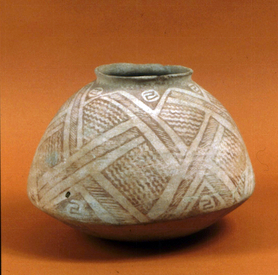

EARLY MOGOLLON POTTERY ca. 1000 PE

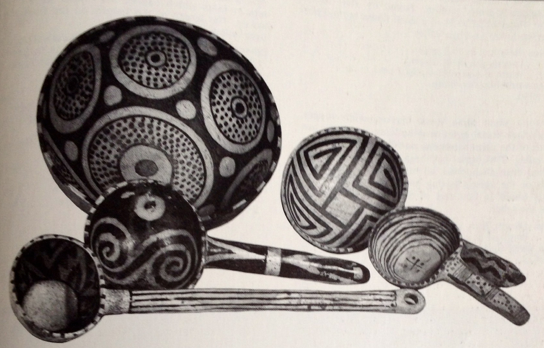

MIMBRES, 800-1200 PE

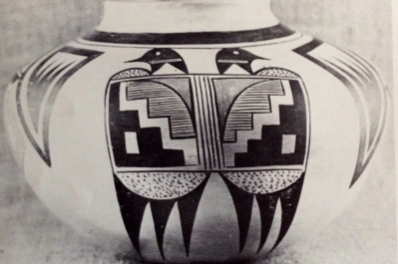

The Mimbres group is associated with the Mogollon clan, and branched off from them in the Mimbres Valley in southwestern New Mexico. The earliest Mimbres ware was grouped with the Mogollon, reaching a high point in pottery making in two different periods, the Three Circles Mimbres, (825-1000) and the Classic Mimbres (1000-1200). Mimbres pottery is best known for their black on white and black on cream clay bodies. Their extremely large vessels showed bold designs, displaying animal and human figures, geometric lines and iconographic drawings representing the land around them. Mimbres pottery is also uniquely identified with "killer holes" in the bottom of large bowls. They practiced burying their dead, which included placing a bowl that had a hole in its bottom over the face of the dead. In true Mimbres killer hole pots, the hole was punched from the INSIDE out, which allowed the departed spirit to escape to the next world. Pottery was sacred to the Mimbres, therefore they never traded their ware. While black on white pottery was also produced by the Anasazi, they usually did not paint human figures. If you see figures painted on a black on white pot, it is most likely Mimbres, not Anasazi. The Mimbres died out and their survivors painted their pottery much the same as their neighboring tribes, becoming indistinguishable.

KILLER HOLE MIMBRES POTTERY

MIMBRES POTTERY WITH GEOMETRIC LINES 1200 PE

SALADO, 100-1450 PE

The Salado people produced red pottery in the Arizona area, their culture being a blending of the Mogollon, Hohokam, Sinagua and Anasizi groups. Their work was identified by black and white decorations painted on a red clay body. These people were market driven, producing whatever was "trendy" in the traveling markets. This fundamental philosophy made them tradesmen, and because of this, they borrowed

stylistically in place of necessity. They developed their pottery with polychrome decoration, utilizing the minerals in their area to paint their designs. The height of their pottery making occurred between 1300-1400 PE.

ANASAZI, 1-1350 PE

The Anasazi were the most notable of all the ancient potters of the American Southwest. They initially lived in caves, and by 800 PE, they developed the hi-rise architectural structures we see dotting the Southwest. When people discuss the ancient pottery of our country, they usually associate it with the Anasizi's. The Anasazi were agrarian, built sophisticated canals, and were highly trade oriented. They inhabited a vast territory of 20,000 square miles from Tusayan, Arizona to Mesa Verde, Colorado and to Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Their canals were fed by reservoirs such as the remarkable half million gallon reservoir in Mesa Verde. But, like the other ancient cultures, they did not last long beyond the mid 1300's, probably due to running out of firewood, depleting soil quality and a general loss of resources. They developed a bright white slip that covered their plain grey clay body, and used vegetable and mineral resources to make a dark black slip. Anasazi pottery was decorated in bold geometric patterns on thin walled vessels; their work was sophisticated and complex, demonstrating a bold painterly flair. They traded extensively in Chaco Canyon, developing their functional craft ware into a highly decorated art form. Anasazi potters are famous for their black on white ware, but by the 1200s, they began producing the highly demanded red ware. By the 1300s, they were gone, as were so many other pueblo tribes, but they were always in the lore of the Native Americans. The people of San Ildefonso, Santa Clara and Zuni pueblos lay claim to Anasazi heritage; the Hopi believe they are direct descendants. By the mere fact that so many contemporary Southwest Native cultures claim to be of Anasazi heritage, only suggests the uniqueness of the Anasazi people

PUEBLO II

PUEBLO III

PUEBLO III FIRST MUGS

HOPI and SINAGUA

The Anasazi also produced a yellow to orange ware that signified the development of Hopi pottery. The Hopi believe to be direct descendants of the Anasazi, and believe they developed their yellow ware from their ancestral Anasazi roots. The Sinagua also developed this yellow pottery from Hopi influence. Sinagua, which means, "without water" developed a broad irrigation system, enabling their culture to survive in cliff dwellings in the Flagstaff Arizona area, until they were gone in 1425. In the 1200's, the Anasazi built pueblos on the Hopi mesas, exactly where the Hopi live today, and eventually the Anasazi melded into the Hopi. The Hopi developed their pottery tradition from the Anasazi and Sinagua, displaying the original black on white pottery to the orange red and then yellow polychrome, now identified as Hopi ware. Their work is derived from a heritage that crossed over centuries, rather than a separate unique style. This demonstration of ancestral links to the Anasazi is what makes Hopi pottery so marvelous. The Hopi exist today, breaking the century's sad story of disappearance.

SINAGUA AND EARLY HOPI WARE

THE MODERN ERA

HISTORY OF THE SOUTHWEST NATIVE AMERICAN INDIANS,

14th -19th Century

Spain came to the New World in 1519 with the arrival of Hernon Cortez, who with only 500 men armed with guns, in a few short years conquered Mexico City and the Aztecs. Once this event was made known, thousands of Europeans came to the area looking for the much proclaimed illusive gold. With his great success, he then sent for a larger army, which brought Vasquez Coronado in 1540. This marked the first year the Europeans governed the Southwest. Coronado moved through the territories, beginning at Zuni, then Hopi but found no gold. However, he found the Grand Canyon and modern day Albuquerque, burning villages, raping and pillaging along the way. He then returned to New Spain, (Mexico City) in 1542, never finding any gold, and never to return. But many continued to follow his tracks, converting the natives to Catholicism and outlawing their traditional ways. A great building boom occurred with missions dotting the landscape. Taxes were enforced, starving the Indians until the Indians banned together with armed warriors from neighboring pueblos, and led the Great Revolt of 1680. These fierce Indians attacked the Spanish, killing over 400 men, women, children and priests. They burned missions, marched into Santa Fe and fought off over 1500 Spaniards, who fled to El Paso, New Mexico. But with all this force, the weary Indians finally surrendered after being out maneuvered by Don Diego de Vargas by only 200 soldiers. Now, once again they accepted Catholicism and the Spanish.

By the 18th century, hunger, hardships, smallpox and Navajo and Apache raids broke the spirits of the pueblo people. In 1821, Spain ceded the Southwest to Mexico, but in 1846, the American government entered and took over. They imposed new regulations; the Indians were free of Catholicism, were forced to live in missions that were run by Methodists and Mormons and were forced to join their churches. By the second half of the 19th century, more Americans came into the areas, providing trade with the Indians, which helped the pueblos to survive on some level. However, for the next hundred years, the Indians, once again, were forced to accept new regulations, pay heavy taxes, speak English and become Christians. Yet with all these enforcements, American traders learned about the Indian artists and crafters in order to trade with them; they learned Indian culture, language and customs. Commercialism helped keep a part of the Indian heritage alive.

SOUTHWEST POTTERY OF THE 20th CENTURY

There are nineteen pueblos in New Mexico, one pueblo and one tribe in Arizona, one pueblo in Texas and three reservations that span the Southwest which are recognized by the U.S. Federal government. They are listed as follows:

ACOMA

New Mexico

New Mexico

COCHITI New Mexico

HOPI TRIBE  Arizona

Arizona

ISLETA New Mexico

JEMEZ

New Mexico

New Mexico

LAGUNA New Mexico

New Mexico

MARICOPA&PIMA Arizona

NAMBE

New Mexico

New Mexico

OHKAY OWINGEH New Mexico

PICURIS New Mexico

POJOAQUE

New Mexico

New Mexico

SAN FELIPE New Mexico

New Mexico

SAN ILDEFONSO New Mexico

SANDIA New Mexico

SANTA ANA New Mexico

New Mexico

SANTA CLARA New Mexico

SANTO DOMINGO  New Mexico

New Mexico

TAOS

New Mexico

New Mexico

TESUQUE

New Mexico

New Mexico

YSLETA DEL SUR Texas

ZIA

New Mexico

New Mexico

ZUNI New Mexico

MESCALERO

Apache Reservation, New Mexico

Apache Reservation, New Mexico

JICARILLA

Apache, Reservation, New Mexico

Apache, Reservation, New Mexico

NAVAJO

Reservation, 4 Corners-NM, AZ, UT

Reservation, 4 Corners-NM, AZ, UT

The difference between a pueblo and a reservation originates from the fact that the Pueblo Indians had their land granted to them (as did the Mexican residents of New Mexico) in 1848 in the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hildago between the U.S. and Mexico. Most Indian reservations were established in treaties between the U.S. and the Indian tribes themselves.

For this presentation of Native American Pottery, I will focus on the most influential potters of the pueblos, tribes and reservations of the Southwest. These particular communities have brought forth some of the most famous American potters of the 20th century. Therefore, instead of a brief overview of all twenty five groups, I will present a more in depth discussion of the work produced by these potters, reflecting a comprehensive survey of pottery produced by our Native Americans in the Southwest.

THE SEVEN FAMILIES

In 1974, the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico, had an exhibit of seven family members of pueblo potters, each descended from a celebrated matriarch. This singular exhibit that showcased these potters had a profound effect on the lives of Native American potters. The exhibit propelled these seven families into fame and fortune as leaders in their people's pottery movement. I will be discussing these seven families as well as other renown potters of the Southwest. Many deserving potters from other pueblos did not share in this experience directly, but the impact of this show was a dramatic rise in our country's awareness and appreciation of all Native American pottery.

With each pueblo, I will present the historical information of the community, then introduce the potters who transformed our American Pottery tradition. As attention increased on our Native Americans, people in our own country as well as the world over finally began to comprehend the greatness of the art of our native peoples, a tradition in art that began before any Europeans ever came to our shores.

The Seven Families:

Acoma

San Ildefonso

Santa Clara

Hopi

ACOMA

Acoma people are called the "People of the White Rock", or people of Sky City. This pueblo has the distinction of being the oldest continuously occupied settlement in the U.S. Sky City exists today, still with no electricity or running water. The people who live there go down the mountain with buckets for water as they did for hundreds of years. There is a road now that goes up to the top, and while some continue to walk down the mountain for their water and supplies, many of the people drive up and down with buckets for water and supplies. However, all still live with no electricity. This is a choice, as below the mountain is a settlement of Acoma people who live much the same way as other modern pueblos. Then why do people go up the mountain to live this kind of life? I was very fortunate to visit Acoma and go up the mountain to Sky City. The buildings are beautiful adobe structures with white ladders on the outside, enabling them to climb up the levels or stories of the buildings. This type of architecture is typical of the ancient pueblo structures; access to their multi storied edifices were made via these outdoor ladders, so that during the numerous invasions, the ladders were brought in, keeping the invaders out. People choose to live in Sky City almost as a retreat or spiritual connection to their ancestors. There is a large church with painted walls that is still in use today for weddings and other ceremonies. What was so outstanding about my visit, was that there were potters selling their wares on tables outside their homes. As we know, the ancients had no running water or electricity in their homes, so obviously, these modern day potters are able to produce and fire pottery in much the same way their ancestors did. However, Acoma as well as Zuni potters have moved into electric kiln firings and commercial clay and glazes for some of their non traditional ware. A discussion of this phenomena is at the end of my presentation in the Zuni section.

ACOMA HOUSES IN SKY CITY TODAY

OUTSIDE LADDER ON ACOMA HOME

OUTDOOR BREAD OVEN ACOMA HOME

PRESENT DAY SKY CITY POTTERS

SLIPS USED BY PRESENT DAY ACOMA POTTERS

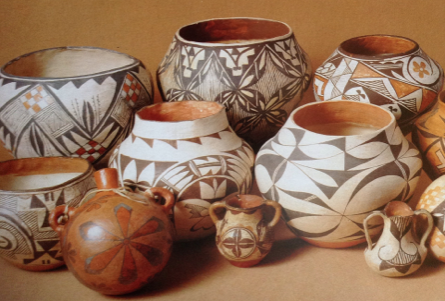

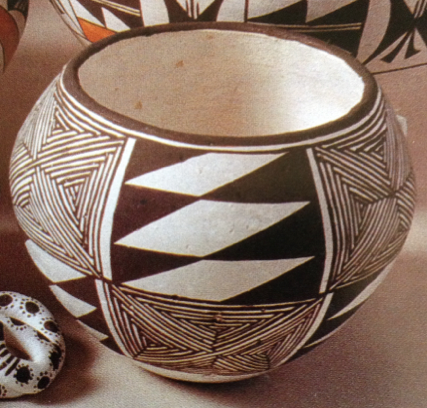

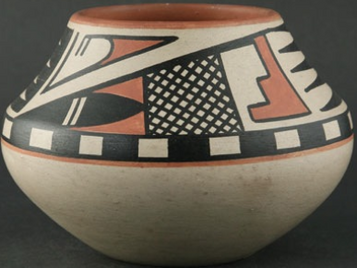

Typical Acoma ware is a white clay body, decorated in red and black slips, with a soft matte texture. In 1880, the railroad brought many tourists to the area, who purchased these vessels, and the Acoma people made work to satisfy this trade. They excelled in "ollas", large jars with dramatic graphic designs. While they no longer use their clay vessels for storage, using more contemporary pots and pans, they continue to make these gorgeous pots for the tourist trade.

TRADITIONAL ACOMA POTTERY

LUCY LEWIS, 1900?-1992

Lucy Lewis is one of the most famous potters of the 20th century. She began making pottery at age seven and by the 1940's she had significant attention from collectors for her prehistoric designs on modern pottery. In 1958, Lucy met with Kennith Chapmen from the Museum of New Mexico who suggested to Lucy to employ the ancient Mimbres black on white design onto her pottery. Lucy already had been exposed to ancient Mimbres shards all her life, and this type of decoration was natural to her. Lucy's daughters followed in her steps in pottery making, but the tradition has died out with the grandchildren.

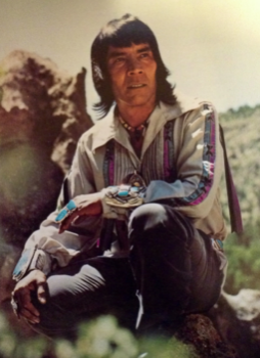

JAYNE SHATZ AND PRESENT DAY SKY CITY POTTER

LUCY LEWIS

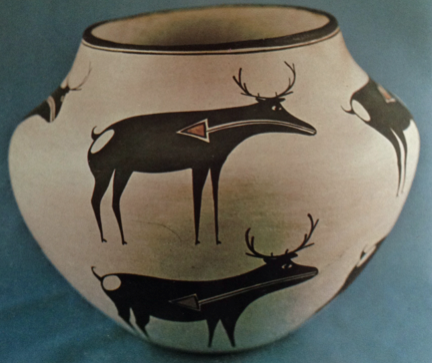

LUCY LEWIS, RED AND BLACK ON WHITE, DEAR WITH HEART DESIGN, 1968

LUCY LEWIS BLACK ON WHITE PREHISTORIC EFFECT

MARIE CHINO, 1907-1982

Marie Chino was as talented as Lucy Lewis, but for some reason did not gain the notoriety that Lucy had. They were friends as well as competitors, oftentimes painting each other's pots with their own designs, creating a famous collaboration. Marie was a prize winner at the first Southwest Indian Fair in 1922, a very prestigious event. Like Lucy, Marie's inspiration germinated from ancient shards around the Acoma pueblo. There is an ancient cave near the pueblo that contained prehistoric shards that Marie and other potters visited for learning ancient designs. Marie had five daughters who pursued pottery making, three of whom gained much recognition, but unfortunately, similarly to Lucy's family, the grandchildren have not continued the pottery making tradition.

MARIE CHINO

MARIE CHINO BLACK ON WHITE. 1972

6 3/4 X 9 3/4 IN.

HOPI

Three Hopi mesas, which are flat toped hills, have nine villages, with the First Mesa and the village of Hano being the most well known in pottery making; this is largely due to the unique clay found in the their mountains. Hopi pottery goes back thousands of years, like the Anasazi, they too claim to be the oldest continuous living settlement at their Third Mesa village of Old Oraibi, which goes back to the twelfth century. Actually, the Hopi Reservation lives on a three thousand square mile island within the great Navajo Reservation, northeast of Flagstaff.

Hopi's Anasazi and Sinagua ancestors spoke different languages; the Hopi today speak a Uto-Aztecan tongue, as do many of the Southwest tribes. Hopi history and religion is intertwined with the Zuni people, with the Zuni's speaking their own language. Therefore, most of the Native Americans in the Southwest speak a common English. Hopi pottery was traded widely from the 700's on, but diminished greatly by the 1800's. However, in the early 19th century, draught and epidemic caused many Hopis to take temporary refuge in Zuni, where they relearned their pottery making traditions from the Zunis. The railroad's presence brought many traders, increasing the need for Indian wares.

Hopi ware was characterized by a white or yellow slip with crazed lines over the ware. Then a local trader asked the Hopis to reproduce their archaic forms of the abandoned first Mesa, Sikyatki, which enabled Hopi potters to gain influence and prestige in their work. By the 1900's the Nampeyo family had achieved great notoriety, defining 20th century Hopi pottery.

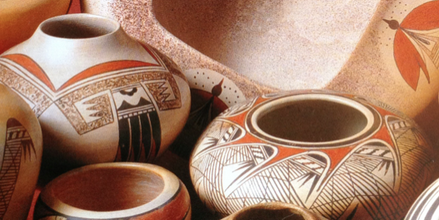

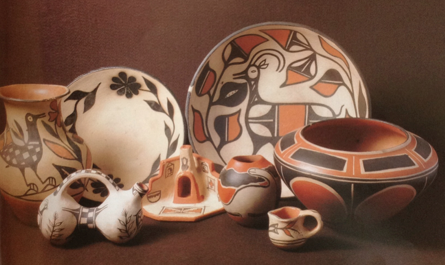

TRADITIONAL HOPI POTTERY

NAMPEYO, 1860-1942

The potter Nampeyo, was born at the first Mesa at Hano. She was producing pottery at a very young age, but the Smithsonian expedition of J. Walter Fewkes in 1896 had unearthed some ancient pottery which he showed to Nampeyo, the wife of one of his workman. She enthusiastically created a Hopi Sikyatki revival of pottery, which inspired other Hopi potters. These ancient Hopi designs and low shouldered forms became the landmark of Nampeyo's pottery and future Hopi potters. In the 1990's Fred Harvey, the entrepreneur of much of the Grand Canyon’s hotels and outer buildings, brought her to the Canyon to demonstrate Hopi pottery making for hotel guests. He then brought her to Chicago at a US exposition where she introduced Southwestern pottery to the world. Nampeyo's three daughters became potters, Fannie becoming famous in her own right. The six generations of Nampeyo descendants are vast, and Hopi pottery is still made today in the traditional way, employing both traditional and contemporary styles. At the Grand Canyon, there is a replica of a traditional Hopi house, which stands as a museum, exhibiting and selling Hopi art and pottery.

NAMPEYO STYLE

NAMPEYO POLYCHROME, 1930

12 1/2 X 8 1/2 IN

FANNIE NAMPEYO, 1900-1987

Nampeyo's three daughters, Annie, Nellie and Fannie, all became accomplished potters, but Fannie Polacca Nampeyo is perhaps the most famous. She produced her work during a period when collectors were seriously collecting signed Southwest pottery. She remained true to traditional vessel construction and design throughout her career. She made coil built pieces and then laboriously burnished the slip painted surfaces; the result was a beautiful patina. In the early 1920's she married Vinton Polacca and then pursued her pottery making as an important part of her life. She had worked with her mother, learning the techniques and styles of traditional ware. Fannie was extremely prolific and earned her reputation as an outstanding potter. Her work included black and red slip designs on yellow pottery. Her works have been included in many collections, museums and universities.

FANNIE NAMPEYO, 5 X 8 IN

SANTA CLARA

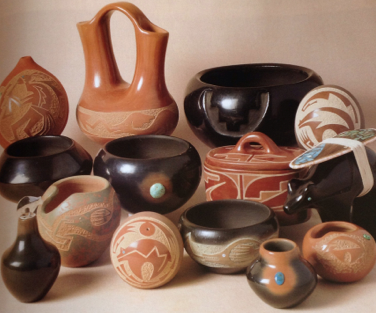

The mesa ruins of Puye are remains from Anasazi settlements that were built on Santa Clara land. About 1500, the Puye settlers joined the people of the Rio Grande, where they met with Coronado's soldiers in 1540, built a mission by 1640 which was burned by 1680. After 1692, these remaining people joined the San Ildefonso clan on Black Mesa and were able to hold off the Spanish until 1696. But, they fell again, and ran off to join forces with the Zuni and Hopi, but by 1702, they returned home to their original territories and built a new mission. Today, the people of Santa Clara live and work in a good relationship with the Hispanic population in the area; they farm, some work in Los Alamos and many make pottery. They have become extremely prolific potters, over 200 potters turning out their very famous black ware and red ware at very high prices. When the Smithsonian made their expeditions in the late 1800's, they were purchasing undecorated black and red storage jars. The famous Bear Claw design of the Santa Clara pueblo did not become wide spread on their ware until about the 1900's. What changed their production was the railroad and tourists. The Santa Clara potters began producing multitudes of small pieces for the tourist trade. These pots were functional, such as pitchers, vases, cups, even some animal figurines, boosting their economy and putting the pueblo on the map of great southwest pottery.

FANNY NAMPEYO

EARLY SANTA CLARA BLACK WARE

MARGARET GUTIERREZ

MARGARET TAFOYA

GRACE MEDICINE FLOWER

JOSEPH LONEWOLF

HOHOKAM, 100-1450 PE

The Hohokam culture existed in a similar time frame as the Mogollon, also disappearing similarly about 1450 PE. Like their neighboring Mogollon, the Hohokam built large settlements, but did not live in large dense pueblos. Rather, they lived in expansive rancheros, with single family units around the present day area of Snake Town, Phoenix, AZ. While they lived widely dispersed, they only contained an area of 400 acres, with a small population of 500. We might relate to these people as living in a suburbs of a major city, the major sites being settled by the Mogollon. They were farmers with an intricate canal system, developing their lands for over 1000 years. They cremated their dead, leaving no burial sites. Their ware was termed Plainware, representing their Plains area, in a buff clay body with red designs. This coarse pottery was well fired and made excellent cooking vessels. In time they they blended into the Salado and Sinagua people.

HOHOKAM 900-1100 PE, AZ

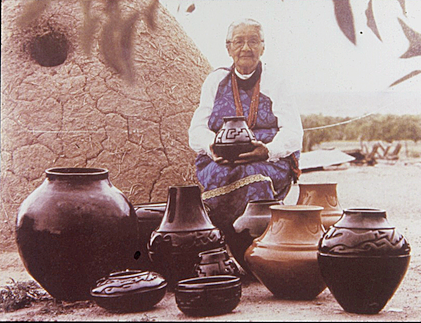

LUCY LEWIS

FANNIE NAMPEYO

DAISY NAMPEYO 1935

SANTA CLARA BLACK CARVED WARE

MARGARET TAFOYA

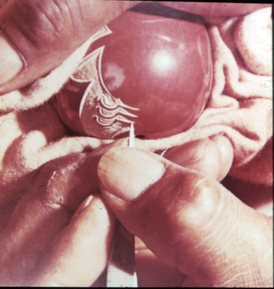

JOSEPH LONEWOLF CARVING POT

SANTA CLARA REDWARE

In the late 1800's the Santa Clara potters fired their pots in an oxidizing pit fire, to a red color, set aside the ones they wanted to remain red, and then refire the others smothered in cow chips, or cow dung, in a reducing fire to turn them into black ware. The pieces were burnished and were very sophisticated in technique and style. The redware was not as popular as the blackware until about the 1930's when the potters began outlining their polychrome designs in white. By the 1940's they added the grey blue slip that has persisted till today as part of the Santa Clara polychrome redware.

VAN GUTIERREZ, 1870-1956

LELA GUTIERREZ, 1874-1966

MARGARET GUTIERREZ, 1936-

LUTHER GUTIERREZ, 1911-1987

The history of the Gutierrez family goes back many generations, with the first potter, Ta-Key-Sane, the great grandfather of Lela Gutierrez, who made pottery for home use. His son then began making more artistic pottery, adding colors to the basic ware. When he died, his son and wife began making pottery together, establishing a husband and wife team, a concept that was to survive through the coming generations. By the time Van began making pottery, his family had many improvements in their lives and their pottery making became their livelihood. When Van married Lela, they made their pots together, Van creating the designs and painting, while Lela made the pots. Then the children, Luther and Margaret continued the family's pottery making, creating some of the most beautiful pottery in the country. With Luther's son and wife, Paul and Dorothy, a different route was established; they started making blackware animal figurines, called mudheads, which are very expressionistic. Their work is very popular today.

GUTIERREZ FAMILY WARE

SERAFINA TAFOYA, 1863-1949

MARAGARET TAFOYA, 1904-2001

By the 1900's, Sera Fina, or Serafina, was the leading potter in Santa Clara. She was a master of large forms, producing huge storage ollas, storage vessels, that were over thirty inches high. While she worked in the pottery, her husband, Geronimo worked in the fields. By the 1920's, her children were adult age and were also working in pottery. There were several tourist events that provided the Tafoya family with extensive sale venues. Serafina and the Tafoya family were becoming as well known as Maria Martinez in the San Ildefonso pueblo, and there was a thirst for Southwest pottery. Fred Harvey Tours ran limousines from Santa Fe to Santa Clara with enthusiastic buyers. In the 1930's, Serafina and her children were selling their work in Taos and Santa Fe, winning many awards. As World War ll ended, the Tafoyas had a family car which enabled them to sell their work all over the Southwest, and by the 1960's, the Tafoya family, from Serafina down to great-great grandchildren became the most prestigious highly priced family of potters in the Southwest.

The Tafoya pottery made a great deal of ware, beginning with Serafina's large ollas. Her work was produced with the highest quality of roundness, smoothness and refinement. Her daughter Margaret, became the most famous of the Tafoya family. She created carved blackware as early as 1922, then moved on to polychrome redware. Her deeply carved black on black pottery generated her great fame. The Bear Claw design, which is synonymous with Santa Clara pottery, is a good luck symbol, because the bears always knew where water was, an essential element to pueblo living. Other symbols on the ware are kiva step, mountains, clear sky and buffalo horn. Margaret is also well known for her large vessels like her mother’s. In the 1960's, Margaret's brother Camilio and his son and daughter, Joseph Lonewolf and Grace Medicine Flower produced intricate miniature pieces, which became the first extremely high priced pottery of the pueblo. Joseph's miniatures have also been cast in solid silver.

The Tafoya family is very large, with over 100 direct descendants of Serafina, more than 70 of them being potters. With the family marrying into other families over the generations, there are 150 potters from the Tafoya clan in the Santa Clara pueblo, creating beautiful work with very high standards.

TAFOYA FAMILY POTTERY

MARGARET AND SERAFINA POTTERY

MARGARET TAFOYA POTTERY

As the pottery on the pueblo continued production, several of the young potters began moving the work into a new design aesthetic. As with many artists, when a successful form of art has evolved, new trends surface, giving the upcoming artists an avenue of exploration and a place within the tradition to call their own. Such was the work produced by Joseph Lonewolf and his sister, Grace Medicine Flower at Santa Clara. Now pieces of turquoise and coral were embedded into the surfaces of the ware, and intricate line design, showcasing the artistry of these potters began to appear on their pots. New color to the pottery was also explored, producing a new Sienna ware that is now part of the traditional Santa Clara oeuvre. Some of the more famous of these potters are from the Naranjo family- Elizabeth, Bernice, Karen, Forest and Dusty Naranjo, Jody Fowell, Mela Youngblood and Stephan Baca.

Experimentation with off set shoulders and undecorated forms, and a large body of innovative work have become the new "tradition" of Santa Clara pottery. Some of todays most ingenious potters emanate from this pueblo.

MODERN SANTA CLARA POTTERY WITH EMBEDDED

TURQUOISE AND SIENNA SLIP

SAN ILDEFONSO

San Ildefonso's Anasazi's ancestors settled in the area in what is now the Bandelier National Monument, a great tourist attraction near Santa Fe. During the 1300's, the families of the San Ildefonso pueblo moved about a mile near their current site. Again, the Spanish found them in 1593, taxed them and developed their mission building until in 1680, the people joined the rebellion and torched Santa Fe, but they did not burn their mission. Spanish General de Vargas restored the Spanish presence in 1692, but San Ildefonso maintained separate for a few years, moved on to the Black Mesa and held the Spanish off from their new home. The Spanish finally retreated, San Ildefonso came down from the Mesa and dictated a new truce. But then they finally burned their mission, De Vargas sent a larger army and pacified San Ildefonso at gunpoint. They settled down to a new lifestyle.

With this quiet life, San Ildefonso began concentrating on pottery, and for the next three hundred years began producing some of the most beautifully executed ware from the Southwest. They produced their traditional polychrome ware, adding red to the upper body, and excelled in all areas of production. As the years moved on, they used various other slips, slightly changing the polychrome, but always maintaining their standards. With all this colorful decoration being pursued, everything changed with Maria and Julian Martinez, who learned how to decorate black ware, and suddenly their work was not only some of the best pottery in the country, but became known throughout the world. A new focus on Native American pottery was bourgeoning.

SAN ILDEFONSO PUEBLO POTTERY PUEBLO POTTERY

MARIA MARTINEZ, 1888-1980

JULIAN MARTINEZ, 1885-1943

By the time Maria was born, her pueblo was in decline. Pottery making was almost gone as inexpensive Spanish tinware replaced pottery for cooking items in the home. Maria's aunt, Nicolasa Montoya was one of the last of the great San Ildefonso potters of that time. Maria grew up watching her aunt make pottery, and by the age of 7, was making pots. Maria was invited to demonstrate her skills at the St. Louis Worlds Fair.

She was already engaged to Julian Martinez, and the couple went to Missouri on the afternoon of their wedding day. At the fair, Maria made and fired her pots, and Julian painted his watercolors, as well as demonstrating pueblo dance customs for people all over the world.

Julian's artistic skills developed with the revival of ancient Pueblo mythological creatures, and he evolved into a great painter of San Ildefonso traditions.

Maria and Julian were making beautiful Santa Clara polychrome ware, and were becoming well known for their work. Then, Edgar Hewett, an archaeologist and anthropologist from the the Museum of New Mexico, found some black shards at San Ildefonso during one his excavations on the pueblo. He was fascinated by these and asked Maria if she could make pottery that looked like these shards. By the winter of 1919-20, Maria and Julian rediscovered the techniques that would produce this black ware, and began making their now famous, black on black pottery. Black on Black pottery is ware that has images that lay in both matt and shiny patterns.

When Hewett asked Maria to work on the black pottery, it was at a time when Julian had already been excavating the area, finding those same shards. By this time he had already developed an interest in this black ware. He kept a sketchbook of the found designs which he showed to Maria; Maria then asked her husband to join her in this new enterprise, which began their legendary collaboration of potter and painter. This new development created great economic changes for the Martinez family as well as the San Ildefonso pueblo as a whole.

Maria and Julian continued to refine their pottery techniques and within a few years were known as the best potters in the area. Maria is distinguished as a technical genius with pots of exceptional symmetry, even thick walls and perfectly unblemished polished surfaces.

Julian was excelling in his painterly influence on Maria's pots. He adapted his prehistoric decorations within a contemporary format. His designs were based on the Avanyu, or the horned water serpent and the Mimbres feather patterns, both of which became synonymous with this new Santa Clara blackware of black highly polished surfaces juxtaposed with matte areas.

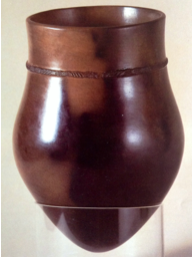

Maria and Julian's black on black pottery became a huge financial success. Soon Maria had to train others in her family to produce the ware, but few were able to achieve her incredible highly polished surfaces and Julians' designs. By the 1930's, Maria was world famous, and her legendary pots put San Ildefonso on the map as a great pottery center of the United States. Maria worked with Julian until he died in 1943, then she worked with daughter- in- law Santana Roybal Martinez, until her death in 1956. Maria continued working with with her son, Popovi Da, until his death in 1971. Later on his son, Tony Da became famous with his black and sienna ware, which required a very difficult firing technique. Others now fire this way, making sienna and black pottery typical of San Ildefonso.

MARIA MARTINEZ BLACK ON BLACK PAINTED WARE

Photo Courtesy of Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery Inc. Tucson- Santa Fe, NM

MARIA AND JULIAN MARTINEZ POLYCHROME POTTERY

Photo Courtesy of Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery Inc. Tucson- Santa Fe, NM

MARIA AND POPOVI POLYCHROME, 1960

TONY DA INCISED SIENNA WARE

MARTINEZ FAMILY POTTERY

THE MODERN ERA

SOUTHWEST NATIVE AMERICAN POTTERS, 14th- 19th Century

ROSE GONZALES, 1900-1989

Rose Gonzaless was another potter of influence from San Ildefonso. While Maria made her name with the painted black on black pottery, Rose became famous with her deeply carved black ware. Her son, Tse-Pe also contributed to this great lineage of potters. At the time Rose was working, carved blackware was being produced at the Santa Clara pueblo, but Rose's work was unique in style. Her more shallow carved edges were rounded and the incised designs were intentionally textured as well as polished in certain areas. This subtle difference makes Rose's pottery more bulbous and softer in appearance. Tse-Pe and his wife followed Roses' work, but as most younger potters do, they experimented with their own stylistic effects. After they divorced, Tse-Pe remarried Jennifer, who also became a signifiant potter. This younger generation worked with odd shapes, inlays, unusual slips in blue, green and even metallic bronze.

MARIA MARTINEZ

GONZALES FAMILY POTTERY, ROSE GONZALES BLACK CARVED POT IN UPPER RIGHT

ROSE GONZALES

SANTO DOMINGO

Santo Domingo is a large pueblo stretching over one hundred square miles across the Rio Grande, NM, with a population of over twenty five hundred. The pueblo is actually known for its jewelry making rather than pottery, but some historic potters sprang from this pueblo. The Indian name of the town is "Guipi", meaning, the unknown. They are relatively quiet and don't encourage tourists. In its history, floods kept destroying the settlement in 1606, 1700 and 1855, each time the people moved to higher ground. After the 1680 revolt, many of the people fled west and helped establish the Laguna Pueblo. From the late 1800's on, the pueblo made black on red and cream polychrome pottery. As the blackware pottery became well known throughout the pueblos, the Santo Domingo potters followed suit, and produced their own version of blackware with distinctive Santo Domingo flowers and leaves as their basic design. Their pottery was not highly prized at that time, but that soon changed. After World War ll, pottery kept diminishing at the pueblo, with their jewelry becoming more sought after. But the potters kept on working, keeping the tradition of pottery making alive.

OLD SANTO DOMINGO POTTERY

ROBERT TENORIO, 1950-

Andrea Ortiz was a potter whose family excelled in jewelry. She allowed her jeweler daughter Juanita to paint on her pottery, and also allowed her grandson, Robert, to work in clay. He attended the Institute of American Indian Arts to become a jeweler with his family, but he was more interested in the pottery division. By the 1970's, Robert was making work that started to attract attention. During the 1980's Robert convinced his sisters and then the whole family to make pottery, which they did, becoming award winning potters. The Tenorio family brought the Santo Domingo pottery tradition back to life, with Robert Tenorio leading the way to great fame.

TENORIO FAMILY POTTERY

NAVAJO TRIBE

The Navajos are the largest tribe in the Southwest. Their population of over 200,000 covers land that extends from Arizona, New Mexico and Utah. The Navajos call themselves "Dine", or, "the people". They probably migrated from areas in Canada into northern New Mexico around 1300-1400 PE, settling in the area known as "Dinetah", dwelling in high mesas and deep canyons. Their early sites are found at Gobernador and Largo Canyons, where they became an agrarian people.

They had many disputes with the residing pueblos in the area, specifically the Utes, which eventually led the Navajos to abandon that area, and settle down more westerly. Again, the Spanish changed everything for the Navajos, making them pay tribute in manufactured goods and agricultural produce. When the big revolt of 1860 occurred, the Navajo tribe joined forces with the pueblos to remove the Spanish, which, lasted only for awhile. In 1692, Spanish rule was reestablished, and many pueblos took refuge in Navajo lands; we saw this same situation with the Hopis, who today still reside within the Navajo Reservation. The Navajos originally did not excel in pottery, rather they became great weavers when they adopted the pueblo looms.

During the second half of the 1700's, Spanish influence became greater in all the territories of the Southwest. In 1821, Mexico won their independence from Spain, and all of New Mexico and its inhabitants came under Mexican rule. A policy of Indian slavery escalated and the Navajos became the Mexicans main targets. Mexican rule ended in 1846 when the northern frontiers were ceded to the U.S., and within the American expansion more frontier conflicts developed between the Indians and the ranchers. By the 1860's there was open warfare, and after several treaties, in 1864, around 9,000 Navajo men, women and children were forced to embark upon a march to Fort Sumner. This has become known as "The Long Walk", a trek of over 300 miles from their homeland to Fort Sumner, in southeastern New Mexico.

The Navajos endured living at the Fort for four years, where after much crop failure, disease, and death, the fort was closed in 1868. In a new treaty, a small tract of land in the original Navajo territory was set aside for Navajo settlement, and surviving Navajos returned home. Rations and some provisions were given to the Navajos, but this was considered the most bitter period in Navajo history.

The Navajo Reservation grew in population as they became familiar with the Trading Post, a way for them the sell their goods. As their community grew, they, alongside all the pueblos in the Southwest, struggled with how to maintain their identity within the modern world.

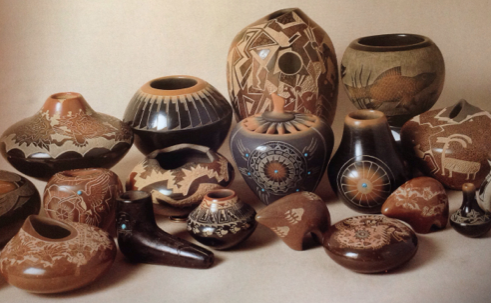

As the Navajos emerged into the twentieth century, so did their pottery. Initially their wares were undecorated utility pieces made by a few families. The leaders of the Trading Posts told the Navajos to start making new pottery to sell alongside their pueblo neighbors, who were creating polychrome decorated ware; their pottery was considered second to their outstanding rugs and jewelry. Soon Navajo pottery developed into beautiful complex vessels, and today's contemporary potters are joining the traditions of the great potters of the Southwest.

GRACE MEDICINE FLOWER POTERY

BERTHA AND SILAS CLAW

ALICE CLING

LUCY McKELVEY

ZUNI PUEBLO

The last pueblo that will be discussed is the Zuni Pueblo, which is actually first area the Spanish entered in the Southwest. In 1539, Coronado went to Zuni in hopes of reaching gold, but instead conquered them in less than an hour. Zuni revolted in 1632, losing the fight. They revolted again in the Great Revolt of 1680, but to no avail, fleeing into the hills. They finally came down and surrendered; they had been attacked by the Apache, and decided that Spanish rule was better than Apache slaughter.

Today, Zuni has entered the Modern age, quietly moving towards the future. It was such a wonderful experience for me and my husband, when we spent three days at Zuni. In Zuni there is a fabulous B&B, The Inn at Halona, run by Frenchman, Roger Thomas. Zuni is one of the few pueblos that has commercial lodging that allows guests to stay inside the pueblo. The B&B was quite beautiful and many Zunis make their livelihood from the B&B and attached grocery. We had the opportunity to meet several residents, and totally enjoyed their hospitality, generosity and graciousness. My host, Roger is very involved in local governing, and knew everyone in the pueblo. Knowing I was a potter, he organized meetings with two of the best known potters in Zuni for me to meet. My time spent with these exceptional people was wondrous; their lifestyle is so different than mine, yet we spoke the same language-CLAY.

Traditional Zuni ware has a pink hue to the clay body, and their black clay slip is actually brown, which is also the main color of their ware. Pre 1930 ware is very precious and highly priced, yet many pots were simply functional home ware. By the 1950, Zuni pottery was in decline, and most Zuni's were producing jewelry. Then the Zuni High School began their pottery classes, and due to several generations of teachers, the great pottery tradition took hold once again.

The first of these teachers was Daisy Hooee, granddaughter of Hopi's, Nampeyo. She married a Zuni man, moved to Zuni and taught at the High School. After Daisy, the pottery classes were taken over by Jennie Laate from Acoma, after she also married and moved to Zuni. In 1985 Josephine Nahohai received a fellowship to teach pottery making. In 1986 The Zuni Tribal Arts & Crafts enterprise sent six Zuni potters to the Smithsonian to view historic Zuni pots. Immediately upon returning home, they were excited to produce and teach pottery.

In the 1990's, Noreen Simplico ran the High School pottery classes, continuing the traditions that she learned there as a child. Noreen was one of the two potters that I met. Her studio in her home shows examples of her beautiful ware, but there is something new in her studio. Noreen creates both traditional and contemporary pottery.

Like so many other Zuni potters, she and her husband drive up into the hills with buckets in their truck. There they dig the precious clay, bringing down buckets of it from the mountain. Once home, they prepare the clay in the traditional ways, and Noreen then makes her pots with ancient coil building methods. She then paints, sculpts additive figurines onto her elaborate forms and fires them in traditional pit fires.

But next to her table of beautiful hand made vessels is her shiny metal electric kiln! On a desk near her clay making area resides her computer, which enables her fingers to reach outside the pueblo. Her world resides between the old and the new.

Her electric fired work helps her make a living. As we talked, I realized that this is no different than many potters I know, who have a "bread and butter" line and then take time to create their one of a kind vessels or sculptures. Noreen's mugs, jars and other forms are slip casted molds that she purchases along with her commercial slips and stains for painting her designs. Her amazing paintings dance along her pieces, and she believes that her painting is what is mostly unique to her commercially formulated ware. On a separate table are her hand built vessels, which I also saw at the Trading Post in town as well as in other galleries, as she is quite well known. She is famous for her sculpted figures which run across the shoulders, neck and covers of her forms. We talked for two hours and I began to understand what had finally changed in the Southwest.

I also saw electric fired ware at the Acoma pueblo. When I was up in Sky City, where there is no electricity or water, there were potters that were selling their ware on tables outside their homes. Some of this work was fired in electric kilns. They get their commercial clays and slips, drive them up to Sky City, make their ware, then drive them down to the main Acoma pueblo where other potters have shared kilns to fire their wares. Alongside this new electric kiln fired ware are traditionally produced Acoma vessels made in the old ways, in pit fires.

I also met Anderson and Avelia Peynetsa. Anderson became one of Zuni's premier potters, sharing his art form with several family members. Now he works solely with his wife, Avelia. At Zuni High, young potters learn about greenware, commercial slips and the electric kiln. Anderson and Avelia dig their own clay and produce their vessels with elaborately painted designs. However like most Zuni and Acoma potters today, they fire their ware in electric kilns, rather than risk the breakage of the pit fires. There is much discussion to this change in pueblo made pottery, and these artists see themselves as both traditional and contemporary. While this discussion will continue for many more years, the work produced by these brilliant potters is breathtaking!

OLD ZUNI MISSION

INN AT HALONA, ZUNI B&B GUEST HOUSE

TRADITIONAL ZUNI POTTERY

NOREEN SIMPLICO

ANDERSON PEYNETSA VESSELS

IN CONCLUSION

In most of our contemporary ceramic circles, we have finally moved on to acknowledge all kinds of ceramic production as "handmade", exhibiting high levels of artistry and craftsmanship. There are so many kinds of innovative methods in the production of ceramics, that we now look at the quality of the work, rather than just how it is made. I learned from Voulkos that a vessel or a clay sculpture doesn't have to have a glaze on it to be considered a ceramic work of art. After all, he used lacquer paint to decorate many of his plates. No one today questions the validity of his work. I moved into patinas in place of traditional glazes on many of my ceramic wall pieces and sculptures, never thinking they are any less ceramic than those finished with fired glazes. The act of rubbing patinas onto my clay surfaces is in fact for me very similar to the ancient potters of the Southwest, who burnished and polished different colored slips onto their wares.

So ends this discussion of our Southwest Native American potters. The story of our country's ceramic origins is great and vast, as I only touched upon one facet of our heritage. As we learn more about the contribution of so many of our nation's ancestors, we begin to see the enormously varied art form of what we call American Pottery. Our ceramic tradition goes back centuries and tells a story of not only the unique complexity of ceramic work produced in our country, but the continual unfolding legacy of the diverse American profile.

Both of these photos are the Photo Courtesy of Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery Inc. Tucson- Santa Fe, NM