JAYNE SHATZ POTTERY

PhD-Prehistoric Ceramics

MA- Pottery and Sculpture

BA - Art History

© 2009 Jayne E. Shatz

THE FIRST POT, HOW IT ALL BEGAN

One Evening at the Close of Ramadan

ere the better Moon arose,

In that old Potter's shop I stood alone

With the clay Population round in rows

And, strange to tell, among that Earthen Lot,

Some could articulate, while others not:

And suddenly one more impatient cried

"Who is the Potter, pray, and who the Pot?”

The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

As a working ceramist and historian, I often contemplate the origins of pottery making. What interests me in particular, is not only where the first coiled pots were produced and how the techniques of pottery making evolved, but also what factors contributed to the development and growth of this boundless art form. For the answers to these questions, we must look back into ancient history.

The origins of pottery making emerged around 30,000 years ago during the Paleolithic Ice Age. Towards the end of this era a major shift occurred when the glaciers receded and a warm climate emerged. For centuries, the hunter-gatherers roamed the landscape, eventually transforming their nomadic existence from this warming transition. They abandoned the support of large clans and settled down to an agrarian lifestyle in individual homesteads. They transcended into the Neolithic farmers of 10th century BC and embarked upon the production of pottery making, spawning a tradition that would embrace the art world for the next 12,000 years.

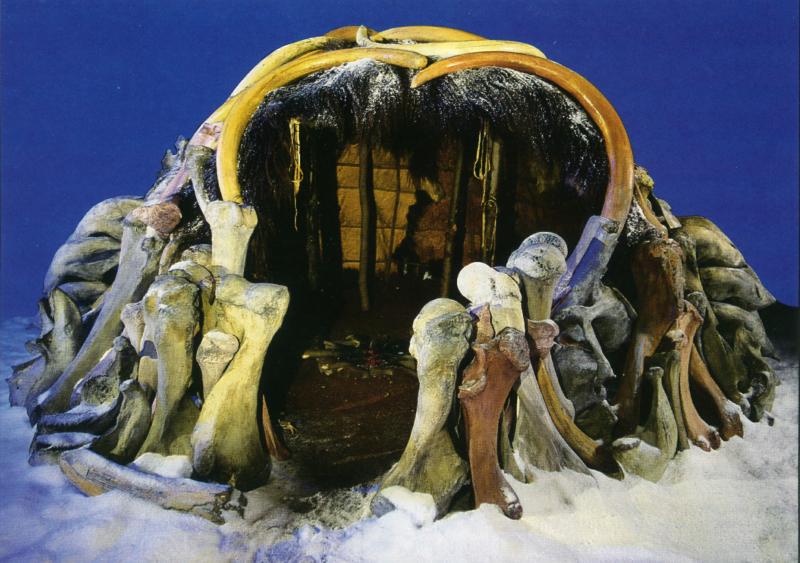

Clay storage and cooking vessels were not part of the Paleolithic hunter’s toolkit. These nomads traveled the routes of the animals they pursued and searched for winter caves in which to live. During the warm weather, they negotiated rivers and built temporary seasonal huts.

They produced reed and gourd baskets, leather bags and carved wood and bone bowls. These objects were strong, lightweight and could travel easily. While these containers served a purpose, they were limited in size and shape, and were unusable for cooking with fire.

They produced reed and gourd baskets, leather bags and carved wood and bone bowls. These objects were strong, lightweight and could travel easily. While these containers served a purpose, they were limited in size and shape, and were unusable for cooking with fire.

As the Paleolithic period came to a close, a new era burgeoned on the horizon. The Neolithic period (10,000BC-2,000BC) spawned the rise of the individual. Farming communities based on single families emerged, creating a new sense of stability. The continuous days of wandering ended. This sedentary lifestyle required increased storage facilities and the need for fired pottery become apparent.

The Neolithic period’s art is defined by the presence of polished stone tools, shell and stone beads, and monochrome painted pottery. Early archaeological diggings surfaced coil built pots produced in Japan between the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods (12,000-2,000 BC). The discovery of the beautiful Joman Pottery established Japan as one of the earliest provinces of Neolithic coiled pottery.

As civilization advanced from the Paleolithic hunter/gatherers to that of the settled Neolithic, more changes in the culture occurred. Where once the vast woods and forests were the food sources for an entire clan, now a small plot of land offered farming and livestock opportunities for a single family unit. Villages flourished to support these homesteads.

Farmers transplanted grains such as barley, alfalfa, oats, and wheat from the wild and stockpiled them in storage vessels. Animals such as pig, fowl, goat, sheep, and dog were domesticated, and by 8,000 BC, cattle were being bred as livestock. Houses became more permanent, built with wood, sun dried bricks, plastered floors and painted walls. Stone tools, polished axe blades, hoes, and barbed harpoons were part of the quickly evolving Neolithic tool kit. This escalating agrarian culture required storage vessels that could winter over food and hold liquids, creating a greater demand for fired pottery.

Established container forms and basket making techniques laid the foundation for coil built pottery. Basketry was an art form that developed earlier than coil built pottery. The very nature of creating woven mats and baskets is from the accessibility of natural fibers that developed by tying objects together with string made from both animal and vegetable materials. Tying, wrapping, and then plaiting (braiding) string, jute, and gut, were the early processes of basketry.

Our prehistoric ancestors discovered that putting these tied sections closer together formed a more solid object. They pressed wet clay inside some of these basket forms, making them watertight. This created the original decoration of impressed designs upon the surface of the clay.

This backdrop set in motion the fabrication of coil built pottery. There are some historians that believe the origins of fired pottery evolved from an accident. They presume that a clay lined basket was on the edge of a firepit and fell in, hence the fired pot emerged. However, there are many archeologists and historians that believe the development of fired pottery was more intentional than accidental. I am among this group. One can imagine the first potters working with clay strips resembling the fibers employed in their basketry, and using the baskets as a type of mold. These early people were already familiar with the properties of fired clay, having developed firing techniques during the Paleolithic period. They ascertained that once clay lined baskets were fired in a kiln, they would become hard, permanent, water tight and could be used for cooking. There were marvelous objects in nature in which to view as containers, providing stimulation for various shapes, such as carcasses, gourds and eggs.

Spirals were one of the first decorative patterns used. This pattern is displayed in common snail shells and local vegetation. Ornamental spirals were already in use during the Paleolithic period, as evidenced by the carved patterns on their bone and ivory tools and sculptures. Prehistoric potters began to employ these motifs onto their pottery.

Early potters shaped their first small vessels with fingers in a pinching fashion, and then built up the sides with strips or coils of clay, like primitive basketry. Then the pots were shaped with a type of spatula that could have been made from wood or bone. They burnished the walls to reduce porosity and create a shine. Sometimes a smooth liquid clay (terrasigillata) of a contrasting color was carefully prepared and then applied to the pots, creating the first painted pots. Other kinds of decoration besides burnishing and liquid clay slip were the application of spirals, coils, impressed patterns, stamped dies and figurative paintings. They used mineral pigments such as hematite and manganese, which were the same earthy materials the artists of the Paleolithic era used to paint cave walls.

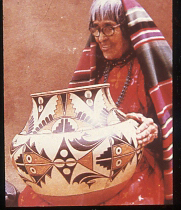

The Neolithic craftsmen began specializing in their tasks to such an extent that they became "professionals" and artisans. The life of the potter focused around specific tasks such as preparing clay, making pots, and firing kilns. Women made the pots for the family, sometimes creating especially beautiful vessels for ceremonial purposes, such as libations to the gods or offerings to the dead. She fired her pots in simple kilns or ovens that later were used to bake her dinner. She also produced most of the basketry and weaving.

Each village and household was self-supporting, mostly subsisting on farming. Their land was cultivated, animals domesticated, with spinning, weaving, pottery and basket making as household chores. As communities matured with an expansion in homesteading and crafts, feelings of hostility that coincide with the possession of land and a sense of ownership escalated, creating the attitude of territorialism. This new independent perspective sadly created a situation of "conquer and own", changing the complexion of the early peaceful Neolithic world to one of power, greed and warfare.

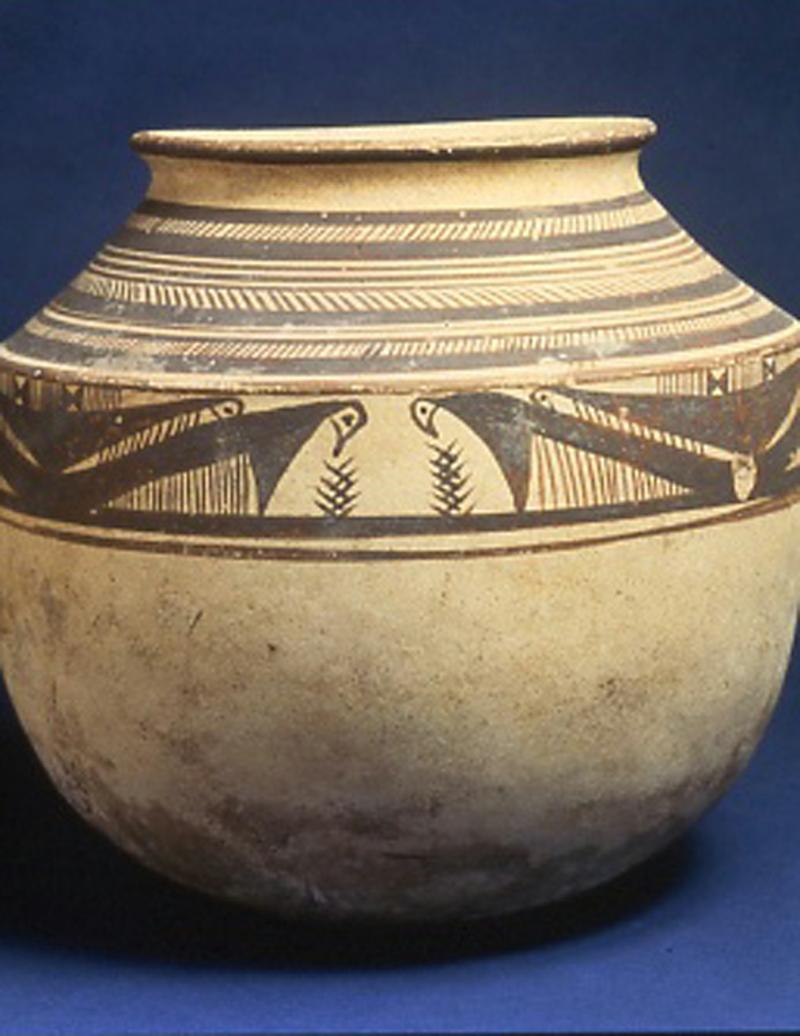

Now that we understand the development of fired pottery, we can examine some of the famous Neolithic pottery making centers. As discussed before, the Japanese Jomon period produced some of the finest pottery of the period. Jomon means “cord markings”. This society’s pottery was distinguished by its rope-like designs that were incised or impressed into their pottery. The pottery was fired at low temperatures and was oftentimes fashioned by women in the community. Toward the middle of the Jomon period, the pottery became very sophisticated, with zealously spiraling coils. Individual communities distinguished themselves by specific designs and patterns on their pottery. I find these vessels to be some of the most beautiful examples of the world’s pottery oeuvre.

Because the Far and Middle East were in close proximity to one another, they developed their agrarian societies simultaneously. They shared a moderate climate and soil fertility, essential factors to the infrastructure of those civilizations. It is no surprise that pottery making evolved concurrently in these two regions.

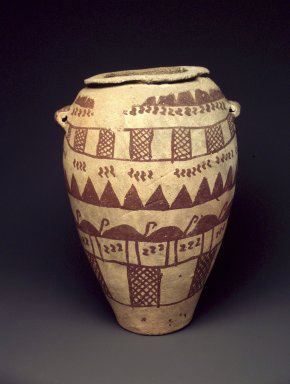

The Hassuna Period (5,000 BC) is a superb example of the furthering development of pottery making in the Middle East.

At this time in the northern Mesopotamia area of Assyria, the prominent pottery centers at Nineveh and Tell Hassuna emerged.

The notable Samarra ware was manufactured in the fertile land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in the southwestern part of Mesopotamia.

The Samarrans developed a very complex pottery manufacture that employed a two story kiln, polychrome painting with geometric decoration, and firings that reached a temperature of about 2,192 degrees Farenheit. Pottery became increasingly important and was viewed as a status or prestige item that represented the sophistication of their culture.

With the final recession of the glaciers in 6,000 BC, the separation of the islands and continents was completed. Consequently, the increasingly rising temperature became much the same as it is today. The seas rose with the melting glaciers, and boats became widely used as a new source of transportation, creating large fishing industries. A new and adventurous sea life bridged many people across the seas with increased avenues of communication and trade. The pottery produced in Japan and Mesopotamia during this period of expansion was widely exported throughout the world by a progressively changing transportation system. A voluminous industry of mass produced ceramics quickly transpired.

In the Mesopotamian region, the Nile oasis was protected on all sides by desert, but the Tigris Euphrates River Valley was open on the North, South, East, and West to invasions.Therefore, the Nile River Valley remained stable while the Tigris Euphrates culture was continually in turmoil and transition. As barbarians invaded from the North, they became conquerors, and then rulers. This added to the increasing warring tribes of the Neolithic culture, with an expanding need for weapon development. The yearning for one’s mastery over another ensued. The constancy for weapons, power, and war emerged in the Neolithic heart and ultimately in their art.

Pottery making developed from the production of simple containers for food stuffs to the resourceful trademarks of a society. Ceramics ultimately became part of civilization’s artistic fabric.

As a contemporary potter, I am amazed to share a commonality with these prehistoric artisans. Now, thousands of years later, as I shape my ware, I have similar cosiderations to the first potters of antiquity. Our lives are so different, yet the formula for good pottery making is the same. Pottery is a very complex craft, requiring careful thought of technique and form. Unlike a representational sculptor, who models the human or animal figure from life, the potter must construct a pot from the mind, in reverse, starting from the bottom of the pot to the top. We work with a purely malleable substance, that sometimes feels as if it has a life of its own. We construct this pliable mass as true creators of form. Possibly this is why in literature, poetry, and spiritual reflection, the potter is seen metaphorically as the Creator of all things. Potters are the designers of form like the Mesopotamian Goddess Aruru who pinched off clay to create primitive man. The Hebrews state in one of their passages, "we are the clay and thou our potter, and we are all the work of thy hand".

ICE AGE HUT RECONSTRUCTION

JOMON POTTERY, JAPAN

JOMON POTTERY, JAPAN

MID EAST BURIEL VESSEL 2500 BPE

In 7,000 BC an early pottery center was established in Mesopotamia in the Zagros Mountains region, an area in the southern Middle East. Pottery was recognized as such an important element of this Neolithic society, that decorated motifs formed the basis for chronological sub divisions of the culture. There is a threefold division of Early, Middle, and Late Neolithic phases; the basic trend in decorative change is the varying use of the incised line. As this line developed from simple bands to spirals and then more complex floral and figurative renderings, a distinction in the evolving Neolithic tradition was established.

NEOLITHIC JAR, PAINTED POTTERY

INCISED JAR, HASSUNA, 6000-5500 BPE

HALAF, PAINTED BOWL 5000 BPE

HALAF, TERRACOTTA, 5000 BPE

There was a change in the ceramic tradition with the disappearance of women producing ceramics for a community’s basic needs to ceramics being developed for manufacture. By 5,000 BC, the potter's wheel was widely in use, and men began taking over what was once women’s work. Foot rings were added to the bottoms of pots, displaying a refinement to the work. No longer was pottery a domestic craft; it expanded into a major industry. As time pressed forward, ceramics continued to reflect a culture’s artistic, philosophical and political temperment. In Greece, pottery evolved into a high art form, reflecting the stories and myths of a culture. In Europe and Russia, great industrial ceramic factories emerged in mass production, placing ceramics on everyone’s table.

The varied contributions of the United States were demonstrated by its Neolithic Native American pottery to the development of its art potteries and the eventual emergence of the post war Studio Potter, foraging a new frontier in the ceramic field.

ABBASID, IRAQ, 800 PE

NISHSAPUR DISH 900 PE

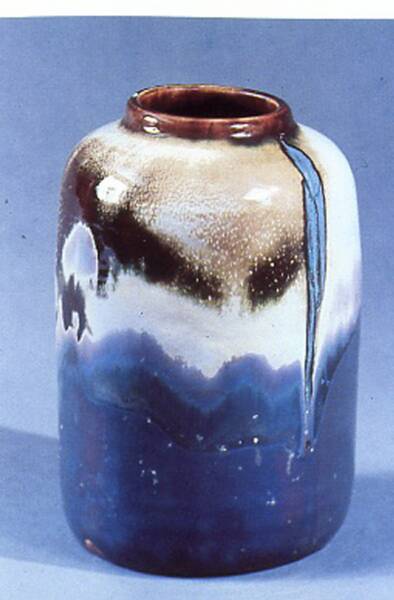

KATARO SHIRAYAMADANI,1900

ROOKWOOD POTTERY, USA

NATIVE AMERICAN KIVA WARE, 1770

MARY CHASE PERRY, PEWABIC POTTERY, DETROIT, MI, 1929

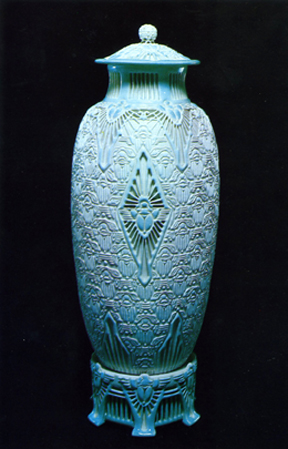

ADELAIDE ALSOP ROBINEAU,

SCARAB VASE, SYRACUSE, NY, 1910

MARIA MARTINEZ, SAN ILDEFONSO, NM

MARTINEZ, SAN ILDEFONSO, NM,

BLACK ON BLACK, 1935

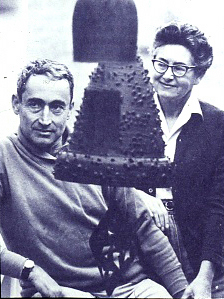

GERTRUDE AND OTTO NATZLER

NATZLERS FOOTED BOWL, 1935

FRAN SIMCHES CHEST, 1972

SIMCHES, BOX 1971

IRA MESSING 1975

IRA MESSING, SINK, 1983

The Paleolithic travelers did not keep clay storage vessels, as they were heavy and too fragile for constant traveling. However, they were versatile with the ceramic medium and they knew how to fire kilns. Clay was modeled and fired as early as 27,000 BC for the production of ceremonial fertility objects, the venus figurines. These sculptures were fired in small simple clay kilns found in the huts of special individuals, presumably the shamens of the clans. (Refer to my article “Ice Age Ceramics,” Ceramics Monthly, February, 1992, pp.78-79).

DOLNI VESTONICE, VENUS FIGURINE

27,000 BPE, 9 " h

Early primitive potters were knowledgeable of the alteration of clay color from the effects of fire. They learned that clay fired at high temperatures with a supply of oxygen produced a red surface; when the oxygen was reduced, the result was black. They produced a black ware by covering the pot with chaff or other organic vegetable matter. Local clays react differently and the difficulty of forecasting surface color must have been one of the most frustrating aspects of pottery production for the early potters. Sound familiar? They fired their pottery in beehive shaped ovens that they also used for cooking. Oftentimes, they placed the pottery in an open hearth covered with brushwood, with temperatures climbing to about 800 degrees F. As the crafts of pottery and kiln building continued to develop, pottery became one of the most important treasures of the Neolithic people.

LASCAUX, DORDOGNE, BISONS, 15,000 BPE