AARON'S LAST STUDIO

"Aaron, please, let me help you. I can vacuum the basement so you can work, and then we'll go buy a dehumidifier. By this afternoon I can have your tools and wheel washed."

"Jayne, the kiln's not working. I broke the tube assembly when I moved."

"Oh, don't worry about that. I'll fix it. Order a new part from Dennis and I'll install it for you."

Aaron looked at me, deep and hard. I knew everything he was thinking. His sadness, confusion, frustration and anger were reeling in his eyes. Aaron is sick and he is dying. But while he is in this remission-like state and is stabilized for the time being, he wants his life. Part of him is being a potter, and I will do my best to help him accomplish that. Right now, we have to get his studio functioning. If I have to, I will crawl on my hands and knees and scrub down his basement in order to give him a healthier space.

"Give me a vacuum and then go upstairs. I'll call you when the last of the dust has settled."

"Okay. Let me get it out."

He began clearing away piles of junk as he located his shop vac. He started snickering, realizing what a mess his basement and subsequently, his life had become. "It's in here somewhere," he said as he handed me a hose, a nozzle, and then finally the tank.

"A, there's no long tube to attach to the flexible hose."

"Oh, I lost it somewhere," he sheepishly replied. But he looked at me with a familiar twinkle in his eyes, and a smile reached his lips.

"What a slob. Alright, I'll use what you've got. Now, get out of here and let me work."

So, there I was, on my hands and knees after all, crawling along the damp cement floor, cleaning up the accumulation of dirt and dust that would be dangerous to Aaron's delicate lungs. I spent hours down there, moving away old furniture, shop tools, and garden supplies, creating an open space around his wheel. After clearing things away, I vacuumed twice, then sponged down everything to minimize clay dust. This will be the last studio for him to make some pots. It would be safer for him to never touch clay again, but one has choices to make, especially in the face of Death. He knew he could probably live a little longer by not working with clay. It was suggested that he leave his job and home and move to New York City where he could have better hospital care than what was available in Albany. But this was Aaron's life, and he had the right to live, and then die, the way he chose. He decided to remain at his job as long as he could work, put together his studio and make some pots. He chose to have a glass of wine every once in a while for a treat, and work in his garden to help maintain his sanity. He lived with Death; trying to participate with Life.

A dying man can be very ornery at times and test the patience of those that love him. That is how Aaron was. One minute he was loving, the next minute he was impatient and angry. All this was acceptable, except for his coldness. The cruelest blade with which he stabbed me was the absence of emotion.

Sometimes I hated him. There were times I could not handle the situation and did not want to see him. I would then feel guilty and run over to be with him, prepared for his verbal abuse. But then there were times he would hold me so close, I thought I'd lose my breath. His eyes would well up in tears and he'd cry about "losing his little life." My heart broke for him and for my own inevitable loss. We cried together, and then made each other smile.

Looking around me, I was pleased with what I saw. I rearranged tables, neatly laid out his tools, found an apron and placed it next to a bag of clay which I had deposited on his wheel head. I then went upstairs to get him.

"Okay. It's ready. C'mon down."

He got off the couch, stretched his arms out wide over his head and encircled me in them.

"You're so good to me, Jayne" he said.

"You better not forget it, big boy", I agreed.

I took his hand and guided him down the narrow basement steps.

Aaron looked at his studio and beamed. His cheeks puffed out like a chipmonk, just as they did when he was younger. His body began to relax and he clapped his hands.

"This is really great! What should I do?"

He turned around asking me, a little afraid that if he touched anything, it would disappear.

"There's the clay, there's your wheel, get a bat, and start throwing", I commanded.

"Great!" He looked around, found the wedging board, smiled, and began. He went over to the clay, picked up a chunk, slapped it on the wedging board, and began kneading. His arms looked powerful, muscles bulging from under his shirt.

"I remember this," he cooed.

It's been so long since he worked in clay. He's known about his illness for eight months now. Before he learned that he had contracted Aids, he and Tom began restoring their house. After spending $15,000 to make the basement watertight for a pottery studio, his disease kept him from fulfilling his dream.

Thump. Thump. Thump. The sound of clay being wedged. His body moved in a dance, clay rocking back and forth on plaster. After wedging enough, he picked up the mass of clay and held it high over his head, as if honoring the event. Moving gracefully to his wheel, he slapped the clay down, situated himself before the lump, wet his hands, and began kicking the wheel.

After a few seconds of centering, he looked up at me and said, "What should I make?" He seemed anxious.

"Why, a pie plate, of course!" I replied.

His smile was wide and beautiful. Then with certainty, he settled down to the business of throwing.

I sat down in front of him, watching his powerful arms tame the sticky animal caught in the grip of his fingers. The clay spun round as his feet moved the flywheel in a methodical, haunting rhythm. It was the heartbeat of his soul, and the flesh of clay sang out that afternoon. Joy spread over his face, traveling down his shoulders to his fingertips, controlling the untamed mass into a form that embodied his spirit. He finished the pie plate, took it off the wheel, stood up and held it high, like a trophy gleaming in the light.

"Get me a camera, Aaron. I've got to photograph you. This is great!"

"Okay, I'll get it", he said as he jumped off the wheel, ran upstairs, and searched for his camera. Finding it, he bolted downstairs again, and began another piece. He worked for a couple of hours like a man untouched by sickness. I photographed his efforts as we laughed, sang, and drunk in the intoxication of the day.

There was no disease that day, everything was as it had always been. There were no viruses, hospitals, blood counts or "T" cells. Pills, tubes, and I.V.'s did not blurr the clarity of our joy. Aaron was not sick that day; there was no AIDS. Aaron, the potter and his best friend, Jayne were just spending a great day together in his studio, making pots.

Time stood still, and the heavy cloud of Death dispersed as Life and Freedom rolled in on a gently flowing bird, flapping its wings in lightness.

It was a moment of grace, and I have it in pictures.

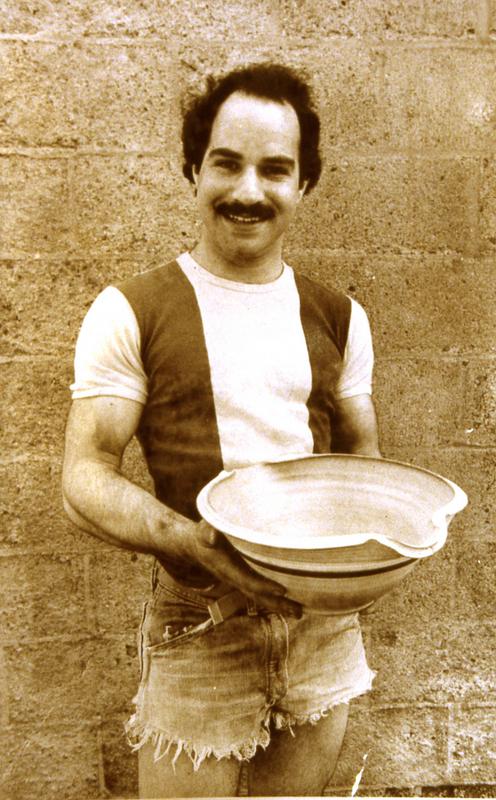

Ira Messing, potter, 1975

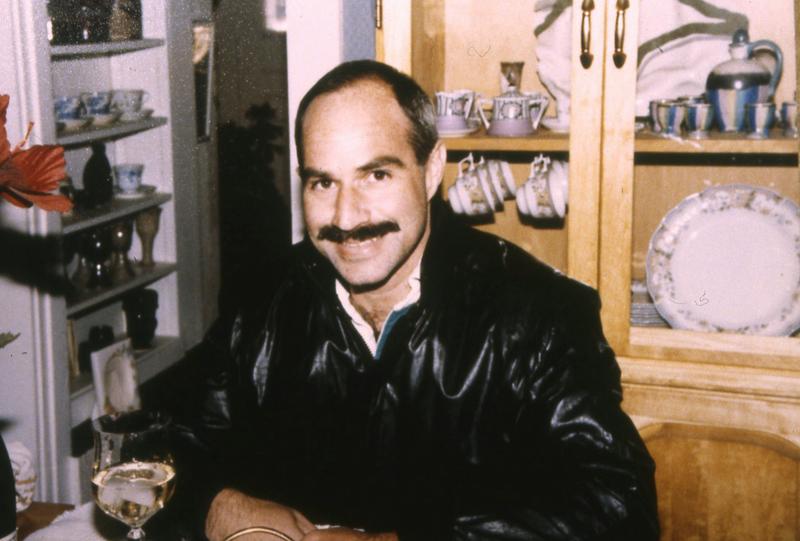

Ira Messing, 1988, potter, one year before he died

This article is a fictionalized story of true events of potter, and long time friend, Ira Messing.

This article was published September 1994 Ceramics Monthly Magazine, pp 110-112